RENÉ DESCARTES, DIGITAL GHOSTS AND A WIND-UP SHITTING DUCK

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enamelling

To keep a drowsy emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

From ‘Sailing to Byzantium’, by W B Yeats.

When René Descartes completed the law degree which his father had forced him to pursue, he was so sick of studying that he resolved that the only book he would ever open again would be the book of the world, and this moment marked the beginning of the philosophical adventure that would write his name into history as one of architects of the scientific revolution. Right at the beginning of this journey, he would make the grotesque error which we still haven’t shaken off today.

After finishing his degree in 1616, Descartes moved to Paris, where he was astonished and impressed by the automata — often life-sized mechanical curiosities mimicking the form and motions of human beings and animals — which were all the rage among the new bourgeoisie of time. A number of skilled manufacturers of such contrivances were based in the city.

Hydraulically and pneumatically powered automata go back thousands of years. The legendary King Solomon surrounded his throne with mechanical animals which hailed his approach: roaring tigers and lowing oxen extending paws and hooves to lift him up; once seated, an eagle placed the crown on his head and a dove brought him a Torah scroll. In the Hellenistic period before the emergence of Rome, Corinth and Rhodes in particular had thriving automation traditions. In Rhodes, as commemorated in Pindar’s seventh Olympic Ode (5th century BC),

The animated figures stand

Adorning every public street

And seem to breathe in stone,

Or move their marble feet.

Yeats’ famous poem ‘Sailing to Byzantium’ references tenth-century accounts of the palace of Emperor Theopilos of Constantinople, wherein stood ‘a tree of gilded bronze, its branches filled with birds, likewise made of bronze gilded over, and these emitted cries appropriate to their species’, as well as mechanical lions which ‘struck the ground with their tails and roared with open mouth and quivering tongue.’

The Hellenic art of the automaton was documented in the writings of the Greek mathematician Hero of Alexandria, and survived through the Medieval Period, with notable examples found in France; for example in the pleasure garden built by Robert II, Count of Artois, at his castle at Hesdin, where his guests would be enchanted by mechanised monkeys, birds, lions and wodwos. Renaissance automata were increasingly powered by clockwork rather than air or water, but after Hero’s treatises were translated into Latin and Italian there was a revival of the fashion for pneumatic or hydraulic automata on the ancient model, adorning the garden grottoes of the nobility. In city centres such as Strasbourg or Prague, spectacular clocks featured automatic figures depicting animals, bell-ringers, and the lives of the saints or of Christ. Leonardo da Vinci famously designed a mechanical knight in the 1490s, and a mechanical lion which was presented to King Francois I in 1515. In the sixteenth century, the workshops supplying the royal courts and chateaux of Europe with these wonders were mainly operated by goldsmiths of the Free Imperial Cities of central Europe, but there were also notable designers in Italy and France. In seventeenth century Paris, the automata on display and for sale as jouets for the new bourgoisie were extraordinarily sophisticated and detailed in their movements — animated figures which danced, painted, played musical instruments or wrote out poems by hand, for example — and now a wider public experienced the fascination of watching a machine behave as if it were a sentient being.

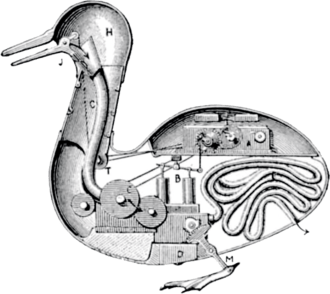

Eventually the illusion would be brought to a more visceral level, to the vast amusement of the public, with Vaucason’s Digesting Duck, which would take food from your hand and then shit out realistic green slime. Vaucason claimed that the duck’s innards housed a miniature chemical laboratory which digested the food. In fact, it just was a trick: there was a separate compartment containing a store of excreta, composed of bread-crumbs mashed with green dye.

∆

Automata are first order simulacra: sacraments to the real, they honour the ineffable qualia, using engineering skill to evoke the reality of living organisms in the imagination. But if machines can be made to reproduce the motions of living creatures, wondered Descartes, then might not living creatures merely be complex machines? With this inversion, the representation jumps its tracks and skips to the second order. Now, rather than reflecting it, the image ‘masks and denatures a profound reality’ (Baudrillard). The mechanistic philosophy developed by Descartes does exactly that. In the four hundred years that it has dominated Western thought, the machine model has proved extremely productive in material terms, but ultimately sterile philosophically and scientifically, misdirecting human awareness away from the reality of nature and the nature of reality. Mechanistic materialism still dominates mainstream thinking today, as exemplified by Richard Dawkins’ notorious phrase in The Selfish Gene (1976) where he describes the human or animal body as a ‘lumbering robot’, a programmable vehicle for the transmission of genes.

This masking and denaturing of reality has had a deeply corrosive effect on human consciousness and our relationship with the rest of the natural world. Machines are not conscious, and while Descartes allowed that animals could perceive and feel, he saw their enactment of pain, fear or distress as automated responses designed to avoid physical damage to the machine — the apparently emotional responses of animals did not denote sentience or suffering any more than a flute-playing automaton could feel the mood of music. This error leads directly to the atrocities of live experimentation and mechanised mass-slaughter of animals in modern economies.

Descartes had to allow that human beings were conscious — after all, his own consciousness was the sole secure conclusion he had been able to draw from his Method of Doubt — cogito, ergo sum — and from there he (generously) extrapolated consciousness to the whole species, as religious doctrine decreed he must. But everything else in existence — including the universe itself — is unconscious, a structure of insentient matter, analogous to a machine.

In the modern era, automation and automatism became the ideal military, industrial and social model. Frederick the Great, king of Prussia from 1740 to 1786, was obsessed with automata, according to Michel Foucault, and ‘put together his armies as a well-oiled clockwork mechanism whose components were robot-like warriors’.

The classical age discovered the body as object and target of power […] The great book of Man-the-Machine was written simultaneously on two registers: the anatomico-metaphysical register, of which Descartes wrote the first pages and which the physicians and philosophers continued, and the technico-political register, which was constituted by a whole set of regulations and by empirical and calculated methods relating to the army, the school and the hospital, for controlling or correcting the operations of the body. These two registers are quite distinct, since it was a question, on one hand, of submission and use and, on the other, of functioning and explanation: there was a useful body and an intelligible body […] The celebrated automata were not only a way of illustrating an organism, they were also political puppets, small-scale models of power: Frederick, the meticulous king of small machines, well-trained regiments and long exercises, was obsessed with them.

— Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 1975

Where machines could replace human labour, they would. Where they couldn’t, humans must be turned into machines.

∆

Mainstream scientific thinking has made no progress on the question of the origins of consciousness: the orthodoxy is that consciousness is epiphenomenal, emerging as a by-product of computational capacity, or even that it is effectively an illusion, a kind of shadow or echo of neural activity. Thus consciousness is nothing more than the fumes of the machine, and this mechanistic model of the human mind in turn gives rise to fantasies common in ‘infantile science fiction’, to borrow McLuhan’s phrase: that the human mind could be compatible with an immortal technological body; or that an information system with sufficient computational capacity might spontaneously awake into consciousness and begin to exercise free will.

After the success of The Age of Intelligent Machines (1990), Ray Kurzweil upped the ante in 1999 with The Age of Spiritual Machines. In this book he argues that ‘spirituality’ is synonymous with consciousness and that therefore a conscious machine may become ‘spiritual’. He betrays an infantile conception of what this might mean, however, when he conjures up images of robots praying or going to church. However, Kurzweil admits that we will never be able to know whether a machine is conscious or not, since it will be trained to simulate consciousness, and in the process may ‘choose’ to simulate spirituality (as, one might add facetiously, do many human church-goers). Really, the only value of this idea, and Kurzweil must know it, is that it gives him a cool oxymoron for his title.

The ‘spiritual machines’ concept is a shallow conceit which recedes into absurdity when we reflect that our science can neither locate nor define consciousness, nor produce any workable theory of how it arises from inanimate matter in an inert universe — the so-called ‘hard problem’ of consciousness. The notion that programming a digital ghost of yourself is equivalent to immortality is therefore, I would say, utterly delusional, a primitive iconolatry born of the desperate and pathetic fear of death with which the machine model tortures its adherents. A narcissistic myth: nothing more than the personification of the echo.

Yeats knew, as Shakespeare did, that you can dedicate your life to art and achieve a kind of immortality. But the work that survives you — hard-wrought as it is with sweat, tears and tortured ingenuity — is no more than a fossilised image of the mind’s hard tissues, a snail’s shell after the snail has died. It may be beautiful, a crafted testament that your soul was here, and that it felt and hurt and marvelled and sang — but it isn’t you.

Yeats uses the idea of a mechanical facsimile as a metaphor for the afterlife of artistic fame, the work continuing to amaze and amuse even when its creator has departed. It is a purely whimsical aspiration; he knows a machine cannot be inhabited by a soul; the golden bird upon a bough, no matter how liquid its song, has no subjective existence. Yeats understands that, but Kurzweil, somehow, doesn’t. The AI prophet wants us to believe that the qualitative mystery of consciousness can be overcome by sheer quantity, and consciousness arise from computational power. A googol, whence Kurzweil’s employer takes its name, is a very big number, 10 to the power of 100. But even a googol of terabytes merely sidesteps the hard problem.

Let’s entertain the notion for a moment, without necessarily accepting it. So, you gather up everything that is or can be known about you, the vast stream of data the machine possesses, all the mined behavioural dividends, all the data from sensors inside your body, you map your connectome with nanobots and programme a machine with it so that the machine thinks and senses like you do, has the same responses and thought processes. Is the machine then you, or merely a very sophisticated simulacrum?

If you have an identical twin, you might share tastes, emotional states, psychological traits, even similar thoughts at times. Your genetic code is identical. But do you share a single consciousness? Are you your twin?

So, you have a problem — you can create the synthetic you, but how do you move into it? How does the machine acquire your subjectivity? Does it awake into consciousness? And if it does, is it your consciousness, and how do you then inhabit it?

As the Buddha knew, there is something beyond the mind. Your mind observes the world, but in meditation, something else observes the observer. Is this an illusion, an intuitive revelation, or a logically necessary assumption — that there is something else which inhabits the mind just as the mind inhabits the body? Just as no Buddhist would make the mistake of believing that they are their body, none would think, either, that they are their mind. Consciousness can detach itself from mind, and experience the mind as the mind experiences the body, as something not itself. Is this meta-observer what we mean by consciousness, or the soul?

Machine intelligence attempts to solve the riddle by recursion. The world as coded by the machine includes a representation of itself, and artificial consciousness is held to be dependent on this simple trick of self-simulation, creating a pseudo-imaginative capacity for prediction and the formulation of intention. But self-simulation by an unconscious entity is still the simulation of an unconscious entity, and to expect it to produce consciousness is an irreducible paradox. It allows the machine to operate in the real world, but in terms of the riddle of consciousness it merely temporises, kicking the hard problem down the road.

It is one thing, in other words, to make a machine that ‘senses’ and even ‘thinks’, but quite another to make a machine which knows it does so — which has a subjective existence. In fact there is now a strong movement in science away from the hard question with its mechanistic assumption that brains generate consciousness; a movement to invert the question, in fact. Rather than mind emerging from matter, it asks, could it be that matter is preceded by mind — that matter, in fact, emerges from mind, rather than mind from unconscious matter? In which case, the brain must be seen rather as a transceiver than a generator of consciousness. The Descartian illusion of the universe as a giant clock is left behind, an inheritance of our earlier ignorance of plasma, fields and currents, and the universe begins to appear not as a machine but as a vast connectome or mind, an intuition suggested both by spectroscopic imagery and the shocks of plasma physics, and consonant with ancient philosophy in the West as in the East. Heraclitus and the Stoics knew — as, I think, did the alchemist Isaac Newton — that the universe is alive, conscious and intelligent. Such an approach promises to be infinitely more fertile, both philosophically and scientifically, than the sterile belief in an inert, entropic universe where consciousness is an accidental byproduct of biology and we are the only conscious agents.

Kurzweil’s claim that, with the advent of artificial consciousness and digital immortality, intelligence will expand outward from this planet to permeate and influence the whole universe seems to me to demonstrate a hubris verging on mental illness, far crazier than anything the Unabomber ever wrote. The great Kurzweil and his Google friends will provide the universe with a mind? Pass the straight-jacket, someone.

René Descartes thought that animal behaviours merely simulated sentience. Now, ironically, the inhabitants of his mechanistic materialist paradigm want us to believe that machines programmed to simulate consciousness can become conscious, and that at that point these learning, self-replicating machines will constitute a new species of life, which will become the dominant species on this planet.

Personally, I find the whole idea about as convincing as a wind-up shitting duck.

NEXT: A DARK AKASHA