In his documentary series The Power of Nightmares: The Rise of the Politics of Fear (2004), Adam Curtis parallels the rise of militant Islam with the ‘neoconservative’ movement in America. Both movements, he argues, represent irrationalist reactions against secular democracy.

The original neoconservatives, including Irving Kristol, Allan Bloom, and Paul Wolfowitz, came together as students of the Chicago Professor of Philosophy Leo Strauss. Strauss, argues Curtis, is the ideological twin of Sayyid Qutb, who returned to Egypt from a period in the United States to found the Moslem Brotherhood. There are strong parallels between these two founding figures. Like Qutb, Strauss abhorred liberalism and secularism, on the grounds that it turned human beings into selfish animals, and believed that society could only be held together by the creation of powerful myths. These consciously constructed myths would of course create an enemy-image – and here Curtis begins to deconstruct the ‘organisation’ known as Al-Qaeda, exposing it as largely the figment of Western intelligence agencies.

The idea that rulers need enemies in order to maintain control of their societies, and that if an enemy is not available they should seek one out or even invent one, goes back to ancient Chinese military theorist Sun Tzu, reappears in Machiavelli, and is developed by George Orwell into an essential part of Emmanuel Goldstein’s ‘Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism’, the book-within-a-book in 1984. Strauss explicitly embraces the same ideas, and so do his neoconservative followers, who at the onset of the new millennium predicated their whole plan for the ‘New American Century’ on a surprise attack by a new enemy – a ‘new Pearl Harbour’. Two months after publication, exactly such an attack occurred in New York, allegedly perpetrated by the political descendants of Qutb.

Curtis argues that both the neoconservatives and the Islamists draw strength from each other; each would be weaker without the other. Both sides create an Overcoming-the-Monster narrative for their people by highlighting the crimes of the ‘enemy’ and exaggerating its evil power, while masking their own. Both sides use fear of this enemy-image to manipulate their own power-base. It is a hostile symbiosis. Sun Tzu, Machiavelli and Orwell would all understand why the neoconservatives would be cheering the re-election of the hardliner Mahmoud Ahmedinejad in Iran in 2009, and why the US financed, trained and armed brutal mercenary ‘Islamist’ insurgencies in Libya and Syria, leading to Al Qaeda 2.0, the manufactured entity known as ISIS or ISIL.

∆

Leo Strauss was born in 1899 in Germany into a conservative Jewish family. In the first World War he was conscripted into the army as an interpreter. He studied philosophy, mathematics and natural sciences at Marburg, Frankfurt, Berlin and Hamburg universities. A political Zionist influenced chiefly by Hermann Cohen, Karl Barth, Franz Rosenzweig, Thomas Hobbes and Martin Heidegger, he met Vladimir Jabotinsky, the hard-line Russian Zionist leader and founder of the Irgun, and published articles in Der Jude and Jüdische Rundschau, German Zionist newspapers. His first research position was at the Berlin Jewish Academy, 1925-8. From there he was picked out and lifted up by the Rockefeller Foundation in 1932.

After studying in Paris and London, in 1937 Strauss took up a post at Colombia University in New York, became a US citizen in 1944 and Professor of Political Philosophy at Chicago University, a position he held until 1968. In 1948 he published On Tyranny, and his publications during the Chicago period include Natural Right and History (1953), Thoughts on Machiavelli (1958), The City and the Man (1964) and Liberalism Ancient and Modern (1968). At Chicago he had a reputation for secretiveness, never gave interviews, and cultivated a cabal of loyal students.

Strauss is undoubtedly a subtle and dialectical thinker, who praised the skill of classical as well as medieval and early modern authors in creating texts which communicated on more than one level, with a dynamic relationship between exoteric and esoteric meaning. Therefore we can expect to see different and even contradictory interpretations of his work. Arguably, one must privilege praxis over theory: the apparent interpretations which underlie the writing, actions and allegiances of his personal disciples must be taken seriously, and where the interpretations of his successors concur with those of his critics we may feel we have found a starting place, at least, for understanding his work.

While Strauss distances himself from the totalitarianisms of the twentieth century (and feared the advent of a tyrannical world state), he is also the enemy of liberalism, to which he paradoxically traces the roots of the twin tyrannies of Communism and National Socialism. Liberalism, he argues in On Tyranny (1948), leads to relativism which leads to nihilism, which expresses itself either in the ‘brutal nihilism’ of Marxist regimes (including National Socialism as a heresy of Marxism) or the ‘gentle nihilism’ of Western liberal democracy, the value-free aimlessness and hedonistic egalitarianism which permeates the West. Writing just after the war in New York, while on a windswept island on the other wide of the Atlantic George Orwell worked on 1984, Strauss too must be credited with some prescience.

Shadia Drury, in her book Leo Strauss and the American Right, argues that Strauss’s aversion to liberal democracy stemmed from his association of ‘the weakness and decadence of Weimar with the rise of Nazism’. In Killing Democracy the Straussian way, Michael Doliner summarises Strauss’s reasoning thus:

[… ] liberalism, dedicated to individual development, has no absolutes, and tolerates such things as abortion, which are one step from Hitler’s gas chambers. Individuals dedicated to their own advancement cannot unite into communities with common beliefs. Consequently liberal democracies are weak and a demagogue can easily overwhelm them. The weakness and nihilism of Weimar led to, or even became, Nazi Germany. For Strauss, American liberal democracy, Weimar revived, is an evil threatening human existence.

National Socialism, like neoconservatism, is utterly repulsed by liberalism, and explicitly seeks to destroy it by any means possible; Strauss asserts that this reaction is inevitable and inevitably takes a totalitarian form.

∆

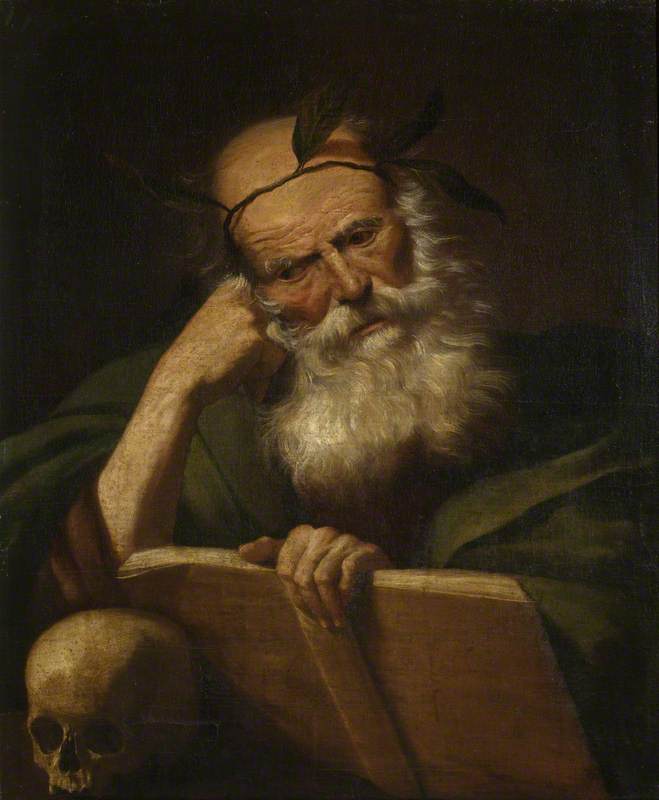

To say that liberalism leads to Nazism is to argue that the prey somehow creates the predator, that the cattle build their own abattoir, both of which statements might seem, if only for a moment, absurd. What is more puzzling is Strauss’s solution. To the problem of liberalism, which is that it leads to totalitarianism, Strauss proposes a brilliant solution: totalitarianism! Strauss’s utopia is based, however, is based not on materialism or racial mysticism but on Plato.

While there are many voices defending Strauss against the linkage of his name with the neoconservative movement in politics and social engineering, we have to acknowledge that the movement initiated by his acolytes, taking what they wanted or needed from his work, came to conquer the dominating heights of the American political and economic landscape: Paul Wolfowitz was Deputy Secretary of Defence under Rumsfeld from 2001 to 2005, one of the war-hawks driving the New American Century’s blood-soaked inaugurations in Iraq and Afghanistan. He went on to become President of the World Bank. Kristol founded The Weekly Standard and became one of the most influential propagandists of his generation. Bloom developed Strauss’s critique of liberal values as exemplified by the sixties counter-culture in his hugely successful work, The Closing of the American Mind.

William Kristol, son of Irving, and Robert Kagan were co-founders of Project for the New American Century, and the co-signatories of the PNAC Statement of Principles manifesto include Paul Wolfowitz, Donald Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney, Elliot Abrams, Donald Kagan, John Ellis Bush, Francis Fukuyama, J Danforth Quayle, Lewis “Scooter” Libby, and Norman Podoretz. The neoconservative movement has had a historical impact on the United States of America, transforming its military principles to pre-emption and unilateralism through the high-tech false flag atrocity they helped to engineer in New York in September 2001. The consequences of this reversal in policy, a series of vicious and cynical wars in the Middle East, have in turn been used to reshape American society, war being the single most potent tool for that purpose. The neoconservative agenda, still holding sway through the Obama White House and Hillary Clinton’s State Department, is explicitly for war – war on a permanent basis, as in 1984 – and we should understand this in the light of neoconservative philosophy. The primary function of war is not to defeat an enemy or acquire territory or resources; the primary value of war in the modern era lies in its effects on the society in whose name it is being waged; above all, war creates the chaos necessary for radical change and far-reaching wealth-transfers to be effected. A never-ending series of sprawling, ambiguous conflicts, allied with controlled media with global reach, creates traumatic impacts on a psycho-social level, rippling across the planet.

∆

According to Shadia Drury, the political programme hidden inside Strauss’s chameleonic political philosophy turns out to be something not so different from National Socialism itself. She argues that Strauss disliked liberalism not only because he thought it must lead to nihilism and thence Nazism. ‘It was the ideals of liberalism itself – secular politics, human rights, equal dignity, and human freedom – that he did not relish. These too he would abolish, for they were the very opposite of what he considered to be the good society. His vision was of a hierarchical society based on natural inequalities and welded together with the fanatical devotion state religion engenders’.

Strauss believed in and proposed a state religion as a way of reviving absolutes, countering free thought, and enforcing a cohesive unity. He argued against a society containing a multiplicity of coexisting religions and goals, which would break the society apart. He thought that ordinary people should not be exposed to reason. To rely on reason is to look into the abyss, for reason provides no comforting absolutes to shield one against the blank sky. Strauss opposed not reason itself, but reason stripped of its secrecy. Reason is for the few, not the many. The Enlightenment, the exposing of reason, was the beginning of the disaster. A reliance on reason, as opposed to religion, produced “modernity” which is nothing more than nihilism made political’ (Doliner).

Strauss’s philosophy is in effect a campaign to undo the disaster of the Enlightenment, and his work is drenched in nostalgic medievalism or neo-feudalism. Such parallels with the thinking of Sayyid Qutb, his Islamist twin, also form a central plank of Curtis’s argument in The Power of Nightmares. There are other historical resonances, too, in Strauss’s vision of the good society.

Strauss develops Plato’s ideal of the Philosopher-King by splitting the two roles with the aim of creating a stable political system. The figureheads of the Straussian state are referred to as ‘gentlemen’, who are ‘drawn from the best families, trained to appear like leaders, imbued with the language of honor and piety.’ Above these, the actual rulers form ‘a secret cabal of atheistic “philosophers”. The people meanwhile, would follow a single state religion. Strauss ‘knew, and believed that all great philosophers knew, that religion is hokum. It was necessary for the masses, but not for the philosophers who […] would secretly rule the state. These atheistic philosophers would supply a Machiavellian wisdom to the gentlemen.’

Drury notes that in attributing wisdom to the philosophers, Strauss is not a conservative, for conservatives believe that the traditions of the society, as they have developed over time, are the repository of wisdom. To that extent Strauss is a revolutionary, proposing government by nihilistic technocrats who force the population to live in a state of designed delusion. Strauss believed ordinary people could not bear the truth and needed religion, so his authoritarian state was good for them, too.

However, in some ways he is only formalising a vision of the society he already lived in. Is this so very different from the way even liberal commentators like Howard Lasswell and Walter Lippmann or the public relations guru and psycho-social engineer Edward Bernays looked at the world? The same question can be asked about Strauss as about Orwell: is Strauss’s ‘philosophy’ a project for the future, or a projection of current reality? Put like this, the difference melts away into semantics, since all futures, real or imagined, take form from what is already present.

What strikes me as most peculiar about Strauss is his language, the strangely antiquated stereotypes of ‘gentlemen’ and ‘cabals’ – and his imaginative projection of himself, as a philosopher, into the first rank of this utopian state in which Plato’s concept of the ‘noble’ lie is consummated in an all-compassing system of delusion. Strauss imagines the philosophers forming a secret society, behind the doors of which they reveal their truths to their students, whom Strauss calls their ‘puppies’. The philosophers train them to understand the real, esoteric meanings hidden in the diversionary exoteric diversions of their works.

The philosophers must form a ruling cabal, and train the gentlemen to appear as leaders, who will model the state religion and propagate their public myths. Their first task is to wean the American public away from liberalism and to drive a wedge between liberalism and democracy.

Democracy can easily be used to suppress liberalism. By demagogic manipulation, democracy can be turned against itself. Since the cabal tells the truth only to its own elite members, and dissembles to everyone else for the purpose of welding together this rigid hierarchical structure, lying to the public is a virtue. Indeed all the gentlemen’s speech to the public, supplied by the philosophers, is for the purpose of manipulation (Doliner).

∆

If the Straussian state is a remedy for nihilism, one might legitimately ask why it is that the nihilists get to rule it, and how that is better? They’re generously sheltering us from ‘the blank sky’, is that it? Kindly making sure that we don’t catch their disease, their curse of rationality, by rolling back the Enlightenment and creating a fog of compulsory ignorance? As a kindness.

The working classes of England responded to the industrial revolution by educating themselves, getting up before dawn to attend debating societies, spending their Sundays attending newspaper-reading groups. In the early nineteenth century, English political traditions were vibrant, and working class culture was dynamic, capable of action and self-sacrifice. The paralysis and destruction of this strong working class culture, with its respect for literacy and hunger for knowledge, is one of the great tragedies of the twentieth century. The neoconservative political philosophy on the other hand seems to be a polemic for a kind of in-growing colonialism, a fascist neo-feudalism, in which an elite turns the rest of the population into ignorant savages so that they can feel better – and safer – about dispossessing them, enslaving them, killing them, raping them, and stealing their children, which is what elites do. It represents a project not merely to disempower but to dehumanise whole populations, by denying them access to reality, freedom of speech and even thought, for whatever ulterior purposes might invade this hollow structure, or indeed gave birth to it.

∆

Naturally, war features prominently in Strauss’s power-structure, and like Machiavelli he acknowledges that its real importance is internal, in tightening the grip of a political or financial elite within a society. ‘Strauss thinks that a political order can be stable only if it is united by an external threat, and following Machiavelli, he maintains that if no external threat exists, then one has to be manufactured’ (Drury). Simultaneously, the word ‘war’ serves to liberate this elite from any moral limitations.

Strauss’s hatred of liberalism is so virulent that he sees the struggle against it as a war, and in war all is fair. For this reason Straussians will use every dirty trick they can think of in the democratic arena in order to defeat liberalism. While doing so they will corrupt democracy itself. But since democracy is only a tool with which to defeat liberalism in order to institute the true Straussian hierarchical society, this is of little import. In the end they will jettison democracy if to do so is expedient.

The Straussians declare war internally and manufacture it externally. In a state of war, everything is justified, and therefore perpetual war can be used to achieve all their aims, because ‘a sense of perpetual crisis and war cements society together with absolute loyalty to the gentlemen’. Meanwhile, ‘The sense of crisis makes the struggle against internal enemies an even more desperate war of “us” against “them”.’

Since domestic politics is also conceived in terms of war, the rules of democracy must not be allowed to prevent victory. Opponents of the ruling cabal, whatever their stripe, are “them”. Indeed, since the cabal of philosophers is deceiving everyone else, even those who have joined the cause out of religious zeal are, in a real sense, “them”. A small circle of initiates who repel the advances of everyone else is a feature of the Straussian state. These initiates are philosophers who rely on reason, and nihilistic reason tells them there are no rules, none, in this domestic battle.

Strauss’s political philosophy, then, is simply the rule of a sociopathic elite, in a state of perpetual psychological warfare with the general population. The Straussians completely eschew morality – the concepts of good and evil, and the rule of law itself, are merely tools – just part of the religion, necessary for social cohesion, but having no meaning in the upper world. The law, religion, morality, are fictions enforced below the line by those who understand that nothing matters. The philosophers who control from behind the curtain and step onto the political stage from time to time to lead openly, are the Nietzschean Übermenschen who rule by merit. For nihilism can only be sustained by a terrifying narcissism.

∆

Perhaps Drury’s and Doliner attacks should be directed more at Strauss’s neoconservative puppies rather than at the philosopher himself. But however obliquely, Strauss tells us what to expect: domination by an oligarchical elite; a permanent state of war; relentless manipulation; and the promotion of a pseudo-ideology concocted to secure permanent power for those who believe in nothing.

There is something I find puzzling about Strauss’s status as a political visionary. There’s something not reactionary but almost Gothic about his Utopia, with its ruling gentlemen, its deluded, religious masses, its cabal of Machiavellian philosophers and their ‘puppies’. Weird though the world he paints is, it seems naggingly familiar.

‘Drawn from the best families, trained to appear like leaders, imbued with the language of honour and piety…’

Is it just that – the elegant description of our own leaders? Is it now?

It reads more like some eighteenth-century aristocratic fantasy.

That’s it! It’s de Sade.

Or de Sade crossed with Goldstein.

Political neoconservatism, whether or not Strauss should completely take responsibility for it, certainly works towards a system of Oligarchical Collectivism and embraces its strategies, exactly as described by Orwell from his narrative point of view rooted in the lower world (apart from Goldstein’s book, and O’Brien’s monologues). The fake enmities, the hostile symbiosis, the all-embracing, totalitarian über-state… the idealisation of slavery, ignorance and war; the subversion of language, the suppression of reason, the invasion of the mind; the citadels of torture and terror; the freedom of thought itself, gone.

The philosopher dreams about ruling the world; the philosopher dreams about the occulting of reason and the repeal of reality; he dreams of enslaving the people by constructing a virtual world for them to live in.

And he dreams of his puppies. After all, the philosopher must prepare the next generation – a philosopher must teach. Must teach them, above all, to conceal their aims, as they go out into the world to recruit their gentlemanly surrogates, through whose lips they will proclaim their noble lies.

REBUILDING AMERICA’S DEFENSES Strategy, Forces and Resources for a New Century. A Report of The Project for the New American Century. September 2000. http://www.newamericancentury.org/RebuildingAmericasDefenses.pdf

Really good essay / treatment! Done a good job of profiling the psychos;

not an easy job. Strauss was your window onto their world .. All in

plain sight, all this time.. hmpht.

A read a book 10 years or so ago by a woman who went to University in

Chicago and studied with Strauss and was a peer to all his followers. She was an

“outsider” student of his [female], but was able to see the outlines of what he

was doing with his circle of favorites; all male; as you describe. She

felt it had an homo-erotic vibe; Plato.. hmpht. (can’t remember the name

of the book right now.)

The way this male group of Strauss may have “joined” together is perhaps

by actual sexual bonding and a real circle of Sado-Masochism? The

woman writer who told her tale of being there with them all, hinted at

that.

Maybe the reason that what you uncovered here is redolent of another time /

place, is because it really is; and these point to the roots of what formed our

alleged “new” “modern” age – that it was rooted in these older crimes by

similar personalities who stayed in power, and taught the next

generation “the score,” as you elude to at the end of the essay?

I was reading some history last night; stories around the alleged

“Elizabeth 1” ; Seems as though her close friend said to be called “Mary

Herbert ; Countess of Pembroke /spouse of the 2nd Earl of Pembroke

[there’s 2 of them with the same name and title and husband , 100 years

apart! ] was pimping out her own relatives to James 1 / 6 .. Strange

story; I don’t have time for it now.. But I suspect they re-wrote real

history around then; changed the genealogies, adopted alt identities of

people they killed.

So this procuress/ best buddy to “Elizabeth One” is one of the suspects

to having written the Shake-his-Spear oeuvre… !?

Anyway.

I think Shake ‘s – Speare was stolen from the real author? It ‘s

certainly come to be agreed among many that the writer wasn’t the “Man from

Stratford.”

You’ve made a very good case for what is likely going on; seems to

explain the data. And yes, I think the same outline traces back some, at

least 400 years. He’s describing what “went down” in the past and making a map of how

it will continue. When those nihilists / tricksters find something that

works, they use it over and over again. They pass it around. If it works, why change it?

Oh, it’s you Pearl. Hi. Oh yeah, his name was suppressed – amazing that it’s held for so long, which in itself tells you a lot about our society and our process of forming history. Emilia Bassano? no. Too young, even younger than Gulielmus Jacques-Pierre of Stratford. And his age screws up the dating of the plays enough as it is. Hamlet was famous by 1589, and it’s nobody’s early work. I haven’t read Joe Atwill’s book, but when he talks about it… well, I’d better not comment, I’ll just write my piece.

Many thanks for linking to my piece. It’s number 12 in a series dealing with a bundle of related topics that might be of interest…

THANKS for that extremely interesting contribution. I think we’re probably thinking the same way. I’ve written about ‘sexual bonding’ in some other chapters, though not in connection with this Chicago group specifically, but the more we learn… You raise Shakespeare, about whom I’ve written a little in ‘Tela Vultus Vibrat’. I’ll post something more on him soon as well. Who is this procuress you mention?