REBIRTH of THE AUTHOR

“There was no one in him; behind his face (which even in the poor paintings of the period is unlike any other) and his words, which were copious, imaginative, and emotional, there was nothing but a little chill, a dream not dreamed by anyone.”

Jorge Luis Borges, in his ultra-short story ‘Everything and Nothing’, plays with the idea that William Shakespeare had the power to assume any identity he chose because he had no identity of his own. Borges’ story is based on the surprising fact that almost nothing is known about one of our civilization’s greatest writers – and that what is known about his life reveals nothing in the least bit interesting or suggestive of genius or literary ability of any kind. William Shakspere (sic) of Stratford-upon-Avon was a mediocrity – a run-of-the-mill businessman, broker and money-lender, a petty, litigious burgher who got a little rich. This paradox gives rise to Borges’ conceit: nothing less dramatic can be imagined than the life of the great dramatist.

Indeed, William Shakespeare is the Invisible Man of his time. His name on a title page or a dedication; a sole, ambiguous attribution by a contemporary; six signatures all spelled different ways. He owned no books, wrote and received no letters. He was never paid for what he wrote; never arrested either, unlike a number of his contemporaries; never questioned or tortured, even after the use of his work in support of the Essex rebellion.

The plays, of course, did not write themselves – but nor were they composed by Gulielmus filius Johannes Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon, who by all indications was barely literate. The universal assumption is that William received a grammar school education, but this is only an assumption since the enrollment records have not survived. William Shakespeare the writer, by contrast, had a world class education, as can easily be deduced from what he wrote.

The name Shakspere is most likely an anglicisation of the Norman Jacques-Pierre, and the wild variety of spellings of the name on extant documents seem to be creative attempts to transcribe it phonetically, with the soft J consistently approximated by ‘Sh’ but the consonant cluster and the final vowel causing all kinds of confusion — thus Shakspere, Shaxper, Shagspur and so on. It’s important to note that the A is always short, as in Jack, in the many versions of the Stratford man’s name that appear in documents. Pronunciation would have approximated to a collocation of ‘shack’ and ‘spare’ in modern orthography.

Shakespeare the poet, on the other hand, was always spelt with the middle E, making the A long and giving us the verb to shake. In 45% of surviving examples, the name was printed with a hyphen — SHAKE-SPEARE — which is a standard way of indicating a pseudonym, as with the anticlerical pamphleteer Martin Mar-Prelate, actually a group of Puritan satirists attacking the Anglican Church. The pseudonym was obviously chosen for its classical connotations: it derives from a soubriquet for the goddess Minerva or the Pallas Athena, the ‘spear-shaker’. The two names are not the same, in spelling, pronunciation or provenance. But they are close enough for confusion, or misdirection.

So William Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon sold his name as an allonym — that is, when a writer uses the name of a real person as cover for their identity. Since ‘Shakespeare’ is already a pseudonym, the misdirection creates a double layer of secrecy. It was only after the deal was made (probably on 1596) that the name ‘William Shake-speare’ began to appear on the title pages of plays.

It’s no surprise that the greatest writer to emerge from that era went to such lengths to disguise his identity. He lived in a dangerous age for writers, the age of the Cecils, Archbishop Whitgift and the English Inquisition; the age of Elizabeth, Queen of Eyes and Ears. Pseudonymity is always tempting for writers: fiction, after all, is multiplicity, the prismatic refraction of personality. An author simultaneously reveals himself in his works and conceals himself behind them. In the case of the great George Orwell, it was to protect his family from his work, and his work from his family. This use of a name-change to delineate separate personal ‘worlds’ might be the common element in every case. Choosing a pseudonym is also an opportunity to create a brand; ‘George Orwell’ was chosen as a quintessentially English name. ‘Will Shake-speare’ was created as not just a nom-de-plume but also, like Martin Mar-Prelate, a nom-de-guerre, chosen for its defiant connotations — the brandishing of a spear before battle — and the identity of ‘William Shakespeare’ remained a mystery: he was the non-entity from Stratford; everything and nothing; everyone and no one.

In time the mystery would give birth not just to J L Borges’ little story but to a fashionable post-modern theory of authorship, usually referred to in Roland Barthes’ formulation as ‘The Death of the Author’ (La Morte de L’auteur). This strange and depersonalising theory arose in the later twentieth century, but may (as a number of commentators have suggested) owe its provenance to the strange disjuncture between the works of William Shakespeare the author and the uninteresting biography of William Shakspere of Stratford. Barthes and other fashionable intellectuals in the nineteen sixties argued that a writer’s life had no relevance whatsoever to the work, and promoted an ideology in which authors are merely unconscious or passive conduits for the culture and the language. If ‘it is the language that speaks’, according to the poet Mallarmé, then the author has no authority, is merely a mouthpiece, and literature is reduced to sociology and linguistics. Like the citizen under Communism, the author is stripped of free will and authentic action; to my mind the theory offers nothing but nostalgia for twentieth century totalitarianism.

In any case, both Barthes and Borges were several decades behind the news: Shakespeare had already been unmasked, not as a non-entity with infinite negative capacity and no identity of his own, but the opposite: very much someone. The Death of the Author had turned out to be just a silly rumour. In the discovery of Shakespeare’s identity, the author really is reborn: the experience of rereading certain Shakespeare plays in the light of the knowledge of the vividly autobiographical nature of these fictions is electric; we have been gifted a whole new writer — an even better one, deeper, more resonant, more real, more important than ever.

As a reader, unless you are a professional scholar, it’s hard to encompass such a vast body of work, and most people end up knowing a handful of plays, up to a dozen or so perhaps, fairly well, and these tend to be the great plays which have really stood the test of time. You may have seen certain plays several times on stage or screen in different productions. Some productions live in the memory forever. If you’re a literature teacher you’ll have taught some of these plays, and there is no better way to become really familiar with a text than to teach it. Those who come to know the texts well tend to develop a strong sense of an individual voice, a singular sensibility and personality behind the plays, as indeed one would with any writer.

That was the case with J Thomas Looney, who taught Shakespeare throughout his career as a school-teacher, and in retirement decided to identify that personality, if at all possible, by drawing up a profile of the author’s discernable characteristics based purely on the works, and trying to find a match among historically documented individuals who were on the scene at the time at the birth of English Renaissance drama in Elizabethan London.

If, like me, you’ve always felt that unsettling disjuncture between the works and their recognised author, it comes as a huge relief to read Looney’s profile; one is immediately struck by its unerring plausibility; it seems to represent a kind of rebirth of the individual in itself. Even before he puts a name on it, tentatively at first, one has a strong sense of the existence of the man who is taking shape: and he really is the opposite in every way of the mediocre stand-in we’d been forced to put up with for so long — a Shakespeare worthy of the name. Looney’s instincts are good:

Altogether we may say his poetic temperament and the exuberance of his poetic fancy mark him as a man much more akin mentally to Byron or Shelley than to the placid Shakespeare suggested by the Stratford tradition. (110)

Looney’s exploratory reflections seem to blast through the banality of the Stratford myth. We’re not looking for a respectable businessman but a wasted genius:

“For example, a man who has produced so large an amount of work of the highest quality, and was not seen doing it, must have passed a considerable part of his life in what would appear to others like doing nothing of any consequence. The record of a wasted genius is, therefore, what we might reasonably look for in any contemporary account of him.” (p110)

We should not expect him to be universally popular:

The poetic genius has always, therefore, been more or less a man apart, whose very aloofness is provocative of hostility in smaller men. (111)

And crucially, as it would turn out, Looney predicted that his relationship with the theatre would in real life turn out to be the opposite of the Stratford man’s: “It is much more reasonable to suppose that the dramatist was one who was prepared to give both himself and his substance to the drama, rather than one who was engaged in extorting a subsistence from it.” (114)

The profile in Looney’s summary goes like this:-

“1. A matured man of recognized genius. 2. Apparently eccentric and mysterious. 3 Of intense sensibility, a man apart. 4 Unconventional 5 Not adequately appreciated 6 Of pronounced and known literary tastes 7 An enthusiast in the world of drama 8 a lyric poet of recognised talent 9 Of superior education — classical — the habitual associate of educated people.”

Looney’s further notes touch on the playwright’s Catholic leanings and loyalties; his feudal, aristocratic perspective; his classical education; his enthusiasm for Italy; his fondness for aristocratic sports; his knowledge of and responsiveness to music; his financial profligacy and improvidence; his conflicted relationships with women.

That’s a quite fully developed profile, to which I don’t think any serious objection could be made. I think most Shakespeare readers would recognise the plausibility of every point. Already we have a somewhat vivid portrait of the man, whoever he is. Out of this wealth of impressions, however, it’s a purely literary consideration which brings Looney the lead he is looking for. Shakespeare would have been known, he argues, if not for the dangerous and consequential enterprise of the plays, then certainly as a lyric poet. In his early work, perhaps… surely there must be some early sonnet or lyric, somewhere, with his name or at least his intitials on it.

“His sonnets, Venus and Adonis and other lyric poems, place him easily amongst the best of the craftsmen in that art. Now, although his contemporaries may not have known that he was producing masterpieces of drama, it is extremely improbable that his production of lyric verse was as completely concealed. He may have hidden lengthy poems like Venus and Adonis or Lucrece, or brought them out under a nom-de-plume. But that no fugitive pieces of lyric verse should ever have gained currency under his own name is hardly possible.” (116)

This was an actionable lead. Surveying the field of Elizabethan lyric poetry in the copious anthologies of the time, he came across an example by Edward de Vere which not only seemed to evince the sinuous logic and concinnity of the sonnets, but was written in the same stanza form as Venus and Adonis, i.e., a six-line stanza in iambic pentameter consisting of an alternately rhymed quatrain and a final rhyming couplet — like the sestet of a Shakespearean sonnet. Looney found that no less than 7 of the 22 surviving lyric poems by de Vere were written in this stanza. The imagery of the poem, too, seemed highly Shakespearean, the haggards metaphor recurring in a number of places in the plays.

This is powerful internal evidence, which Looney was perhaps lucky to stumble on so early in his research, though this is probably more of a testament to his alertness and purposeful methodology. From there, everything falls inexorably into place as the book becomes a literary biography of the man — take him for all in all — who gave us the great works of Shakespeare. Looney’s investigation, Shakespeare Identified in Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (1920) is transparently presented, highly coherent, based on sound reasoning, deep knowledge of the works, and, I would say, a pretty unerring instinct; the book is also very readable and its argument highly persuasive — I’m not sure anyone could come away from it unconvinced that in Vere Looney had found our Shakespeare. His investigation established the identity of the author beyond reasonable doubt, and provided a framework for a century of extremely productive research by literary historians ever since. Some of the most cutting-edge research in recent years has been done by Professor Roger Stritmatter in analysing the marginalia in de Vere’s Geneva Bible and their relationship to the play-texts, and more recently a similar investigation of the library at Audley End, near Saffron Walden in Essex, which is found to contain seven Elizabethan-era books annotated in de Vere’s hand.

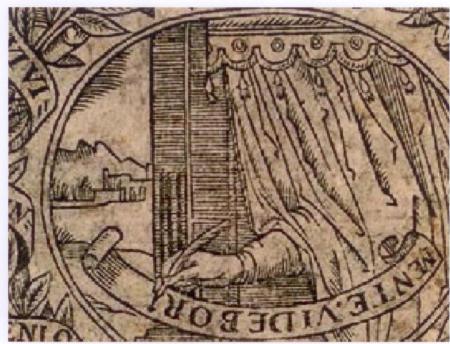

Insiders knew, of course, and more than a few cryptically acknowledged it to posterity and to each other in their works, as Alexander Waugh has documented in his Who Knew? series of videos. Perhaps the most spectacular of such contemporary references is the frontispiece of a book of emblems and devices, Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna (1612), which features a woodcut image reflecting the contemporary awareness of a concealed poet writing for the stage. A hand holding a pen emerges from behind a theatre curtain, and writes (upside down from our perspective to signify a code) the Latin words MENTE VIDEBORI (By the mind I shall be seen). It’s an anagram: NOM TIBI (your name is) DE VERE.

There’s even an intriguing example which has come down to us in the form of a Latin address delivered by the scholar Gabriel Harvey. In the course of a Royal Progress in 1578, Harvey delivered a public address, in Latin, to one of Elizabeth’s courtier-poets, the 28-year-old Earl of Oxford, Edward de Vere, in which he exorted the young man to abandon the pen for the sword and assume his martial destiny.

History tells us that the name William Shakespeare only appears in 1593, as a signature to the dedication of Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis to the earl of Southampton. Certainly the 1593 publication marks the highly successful launch of a ‘new’ writer, whose fame rests on what he wrote (or rewrote) during the last decade of the sixteenth century and the opening years of the seventeenth. But there are hints suggesting that the pseudonym had been in use much earlier, and Harvey’s oration is one of them:

Virtus fronte habitat: Mars occupat ora; Minerva

In dextra latitat: Bellona in corpore regnat:

Martius ardor inest; scintillant lumina: vultus

Tela vibrat: quis non redivivum iuret Achillem?

Valour dwells on thy brow: Mars possesses thy mouth: Minerva

In thy right hand lies hidden; Bellona in thy body reigns:

Warlike passion burns in thee; thine eyes flash: thy countenance

Shakes spears: who would not swear that Achilles was reborn?

Thy countenance shakes spears.

Thy countenance: Shakespeare’s.

A coincidence? Perhaps. Minerva lies hidden in the same passage reduces the odds, broadening the context of secrecy. On the other hand, if Harvey was trying to make the pun, why didn’t he use hastas (spears) rather than tela, which refers to any projectile weapon?

It doesn’t matter; it gives me my title, that’s all. In any case, it should be emphasized that Looney’s argument does not depend on ciphers, codes, or anagrams, but on textual and literary evidence. circumstantial evidence, copious as it is, comes in as corroboration, not as the core argument, though it is remarkable, once the identification is made, how everything falls into place.

The book becomes not just an exercise in literary-historical detection, but a compelling literary biography and creative history of the artist. It’s much more than a dispute about attribution; it’s about the nature of the artist and of art itself/ his relationship to his art. The amazing thing that emerges is just how close the relationship is between the life and the work; the extraordinary extent to which de Vere drew on his own experiences, his own story. De Vere really is the antidote to the ‘Death of the Author’ travesty. His creativity is about as far from a passive conduit as you can imagine; he didn’t just create his individual masterpieces, he did more than anyone else to carve out the space, physical and cultural, in which they would be heard.

The turbulent Earl was one of history’s great individualists, attracting much Puritanical opprobrium for his profligacy and bohemianism, his feuds and love-affairs. De Vere’s creative evolution is unique. In his late teens and early twenties he was Elizabeth’s favourite and a star performer at court, both in his own person and as the Puckish spirit behind brilliantly devised court entertainments. High-born and rebellious, driven, brilliant and reckless, his intimate relationship with the Queen allowed him to escape punishment for acts of defiance which would have had serious consequences for any other courtier. As becomes clear in the extraordinarily personal court drama of Hamlet, he saw himself as having the special status of a court jester or ‘licens’d fool’ in Elizabeth’s court.

After his return from Italy in 1576, he entered a period of intense turbulence in his personal life that would ultimately lead to his banishment from Court in 1581. He had been flirting with expulsion from the magic circle some time, and when disaster came, he responded with a fierce creativity and focus. If the banishment hadn’t happened, the poetic drama would never have become what it did. Looney stresses de Vere’s restlessness with the Court and his increasing Bohemianism, as he calls it. In fact Fisher’s Folly, the mansion de Vere acquired in the theater district after his banishment, and where he brought together writers from all backgrounds, might be called the birthplace of Bohemia avant la lettre, and of a new literary style which emerged from a potent cultural mix, and the contradictions inherent in de Vere’s personal history. The decade which begins with de Vere’s expulsion from court saw a marked change in the character of English poetry, and this change is connected with Lord Oxford’s immersion in London’s burgeoning theatre world. Looney writes:

We have already had to remark his restiveness under all kinds of restraints imposed by the artificiality of court life and his strong bent towards that Bohemian society within which were stirring energetic forces making for reality, mingled with much evil in life and literature.

Quoting from Dean Church’s Life of Spenser, Looney characterizes the ‘Drab Age’ of English poetry as marked by “feebleness, fantastic absurdity, affectation and bad taste … Who could suppose what was preparing under it all? But the dawn was at hand.”

De Vere’s class-apostasy, his banishment and self-exile, has everything to do with this change. Looney cites Philip Sydney’s ‘In Defense of Poesie’ “as representing the earlier, feebler period, and the ‘rude playhouses with their troops of actors, most of them profligate and disreputable’ as being the source of the later and more virile movement.”

The decade of the 80s constitutes “the period immediately following upon [de Vere’s] first poetic output, and it was during these years that he was in active and habitual association with these very troupes of play-actors […] What distinguishes Oxford’s work from contemporary verse is its strength, reality and true refinement. When Philip Sydney learned to ‘look into his heart and write’ he only showed that he had at last learnt a lesson that his rival had been teaching him.”

During the next ten years, 1590-1600, “there burst forth suddenly a new poetry, which with its reality, depth, sweetness and nobleness took the world captive. The poetical aspirations of the Englishmen of the time had found at last adequate interpreters, and their own national and unrivaled expression.”

The smoking gun for de Vere’s authorship is the autobiographical nature of his art. Looney comments somewhere that for someone who kept himself concealed for so long, we are going to end up knowing more about this man than anyone who ever lived. Not only him, of course: almost every major figure in his life, friend or foe. That’s what made him so explosive; courtiers might smirk at the satirical portraits that are everywhere in the plays, but no one outside the Court could be allowed to know the reality of the subject matter. As so often in social elites’ ruthless protection of the status quo, the reality principle itself ends up coming into question — as in Borges’ strange story, or Barthes strange theory.

De Vere’s self portraits were just as unflinching, with plenty of self mockery and agonised regret. The tragedies, after all, his great studies in human folly, centred around his own person, and its not narcissism but rather its opposite. Tragedy is the study of how we destroy ourselves; in Hamlet, Othello and Lear he volunteers himself as model. But this truthfulness, this devotion to reality no matter how painful, is one of the main reasons for the secrecy. It was more than just aristocratic convention and the stigma of print: the identity of the author is crucial to the way his plays would be read. The sonnets, explicitly autobiographical, wouldn’t be read at all, if the Privy Council could help it; when SHAKE-SPEARE’S SONNETS appeared (posthumously) in 1609, the publication was immediately banned by the government and all copies rounded up and destroyed, with only a few dozen known to have survived.

So Shakespeare could only be be read on the condition that we were not put in a position to fully understand him. And this anonymity is what de Vere himself wanted; he makes that very clear in the sonnets. He wants his name, he says in Sonnet 72, to be buried where his body is. He actively wants to be forgotten, though he wants his work to live. And he got his wish, for three hundred years or so, until J T Looney came along. The paradox is that his work would never fully come alive, in my view anyway, until his identity as author was restored.

But even a century later, thanks to the self-interested inertia of academia and the stubborn resistance of commercial interests like The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, Shakespeare’s identity is still not widely known – and this despite the fact that the author is so explosively relevant to our own times.

While de Vere donned his mask out of necessity and circumstance, identity-play was evidently in his blood. How many of the plays feature disguises and assumed identities? From Romeo masked at the Capulet ball, to Hamlet’s ‘antic disposition’, from Portia’s impersonation of a young doctor of law, to Ariel’s terrifying harpy, the delight in disguise is everywhere: cross-dressing and bed-tricks, plays-within-plays and players playing players, and this reflects not just the theatre milieu — the theme of disguise resonates deep within English traditional culture. In the countryside, ‘pagan’ holiday traditions had largely been suppressed by the asphyxiating grasp of the Reformation. Hamlet laments: For O, the hobby-horse is forgot. Stephanie Hopkins-Hughes, at PoliticWorm, explains: “The hobby-horse was a feature in the old mummer’s processions. A man dressed in a horse costume, his identity hidden, would dash at the crowd, singling out individuals whom he thought deserved a public reprimand, while the crowd roared in a combined shout of approval and alarm.”

If these mumming and disguising traditions were anathema to the Reformation, so was theatre, to the nth degree. From the 1590s on, de Vere was fighting a culture war. As ‘one of the wolfish earls so plenteous in the plays themselves’, in Walt Whitman’s razor-sharp intuition about who Shakespeare must really be, he emerged from the old feudal world – but what he bequeathed to modernity survived the eventual closing of the theatres in 1648 and the puritan dictatorship, though it wasn’t until the 19th century that he really started to get the appreciation he deserves. What he embodied, what he fought for was theatre itself, that bright mirror of multiplicity, music and magic, poetry, play and display.

But things went too far. Banished and re-instated, he finally exiled himself from the Court, and in twelve years of seclusion hammered out the final versions of his greatest works, turning them into literary as well as dramatic masterpieces – the great studies in human folly which became famous throughout the world.

The Stratford misdirection has always met with most opposition from writers, directors and other artists. Any real artist knows the labour of art; genius doesn’t just switch itself on and off like a light on a timer. Good writing is hard, long work, the work of an individual who is both equipped and impelled to write by his or her own history and psychology. Art is by definition individualistic and can come only from an individual, as an expression of unique identity. It is not a passive process. Genius is not magic.

∆

Much of the opposition to de Vere’s authorship seems to reflect unconsciously absorbed class prejudice: in other words, inverted snobbery. De Vere is automatically to be despised because of his birth: he is not the Shakespeare we want. We crave an idealized rags-to-riches figure, Mr Nobody from Nowhere, Dick Whittington with a talking cat. Instead what we get is Lord Byron with Faustian gifts and ‘lewd’ friends, the charismatic magnet for a bohemian milieu, in Venice or in London. Sentimentalists don’t want to hear about this reckless aristocrat who got himself imprisoned in the Tower and then banished from Court.

The final trigger was his affair with one of the Queen’s Maids of Honour, resulting in the birth of a bastard son and a vendetta pursued against him by relatives of the lady. The feud spilled onto the streets of Blackfriars in lethal brawls and ambushes, leaving three men dead and de Vere badly wounded. Such was the implosion of the child star of Elizabeth’s court.

Stratford became the chaste birthplace of a miracle, a kind of new Bethlehem, but the Brythonic name ‘Avon’, meaning ‘waters’ or ‘watery place’, as Alexander Waugh has shown, was used poetically at the time to signify not Stratford but Hampton Court: the ‘Sweet Swan of Avon’, Ben Johnson knew, was the poet of Elizabeth’s Versailles.

The ad hoc hypothesis introduced to save Bethlehem is the condition of ‘genius’, which is conceived as something magical. Will Shakspere goes to London and immediately starts producing masterpieces, without the foundation of education, experimentation, or apprentice-work, leaving behind no juvenilia. Twenty years later his genius is suddenly switched back off, and he doesn’t lift a pen again, leaving his unfinished works to be completed by hacks. This is not realistic; it’s a fairytale. The reality is that de Vere’s masterpieces were achieved through a lifetime’s labour and were the result of both exuberant experimentation and painstaking revision. The ‘Shakespeare’ period of the 1590s and early 1600s, which have been traditionally seen as the explosion of Will Shakespeare’s youthful and implausible genius, turns out to have been the maturity of de Vere, who achieved his art through sweat, tears, and, yes, blood too.

It’s not just self-interest and inertia that keeps this patched up paradigm together, and it’s not just class resentment either. There is something deeper here as well, I believe. It’s not just the present-day war on masculinity or nationhood or whiteness that keeps de Vere behind his curtain. I’m talking about the abolition of the individual itself, as a concept, as a reality, as a moral centre – which Marshall McLuhan foresaw as the inevitable effect of the digital age.

The tribe is ruled by superstition. In our celebrity culture, we want to believe that education, discipline and mastery are not preconditions for original creative production. We want to believe in achievement without effort, in ‘genius’ without discipline. That these plays somehow wrote themselves.

De Vere is not the passive mouthpiece for an abstraction.

Today de Vere is no academic footnote, but a challenge to the weaponized stereotyping of contemporary culture. Just as secret performances of Shakespeare’s plays were staged by dissidents in Czechoslovakia under Communist tyranny, so de Vere’s clandestine art can sustain us in our own times. The Borgesian paradox is void: Shakespeare was not nobody. He was a specific individual, unique and unrepeatable. Great art is not produced by impersonal cultural or historical forces, and certainly not by theory. De Vere’s identification is death to the ‘death of the author’ theory; in a word, the rebirth of The Author.

_____________________________________________

NOTES & LINKS

Shakespeare Identified by J Thomas Looney (1920)

https://archive.org/stream/shakespeareident00looniala#page/160/mode/2up/search/dean+church

Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna

Mumming and disguising

It was only later, banished from the Court and his life torn apart by scandals and feuds, that he committed himself to proving he was the greatest writer England had ever or would ever see. And anonymity was now a necessary mask.

, which was, as Alexander Waugh has copiously demonstrated, something of an open secret.

It is admittedly surprising to find these references so early in the timeline; they almost seem like foreshadowings rather than intelligence. I don’t know when Bacon established his scriptorium; but we do know that de Vere was involved in the theatre (as a patron) throughout his adult life, that he had performed in Commedia del Arte in Venice, and returned from his travels in the mid-seventies with detailed descriptions and specifications of the Italian theatres, which became the blueprints for the London theatres, the first of which — ‘The Theatre’– opened in 1576, followed by The Curtain in 77. Harvey’s address, then, was given at a highly significant moment in the development of English theatre — and that, I don’t doubt, was why Elizabeth was not about to follow Harvey’s advice by granting de Vere a military commission. At this point de Vere, who was skilled in the martial arts, was still craving military honour, but the queen had other uses for him. Within three years, however, he had been banished from the Court for his affair with Ann Vavasour, and remained in the cold for two years — during which time he established his own writers’ colony at Fisher’s Folly, the mansion he bought in London’s theatre district, and fully and defiantly embraced his literary destiny and the only identity left to him, as a writer. His anomalous, déclassé status at this intensely creative and dangerous time in his life liberates him, in my view, and puts him on the road to becoming the Shakespeare we know as the greatest literary artist in the English language, regardless of identity. The identification with the non-entity from Stratford-upon Avon always rankled, however, speaking for myself. I remember staring at that face, and wondering how such intense masterpieces could originate in such a non-entity? In my youthful viewpoint, great writers must surely have great personalities, should be contradictory and unpredictable, poetic lovers, beautiful losers and wild idealists. Monsieur Jacques-Pierre from Stratford seemed awfully disappointing in that respect. Edward de Vere, the scandalous seventeenth Earl of Oxford, by contrast, fits the role perfectly, emerging from his aristocratic background to become the first Bohemian in English culture, if you should happen to be looking for one. And while one obviously has to be cognisant of one’s own prejudices, the fact is that the biography of Edward de Vere is very much the biography of a writer, missing only the work itself — the lost oeuvre of Edward de Vere.

The literary scene of the late sixteenth century is full of false names and identifications. Print granted anonymity, the theatre curtain another layer of secrecy, and behind that, the pseudonym, the allonym, or the simple gap on the title page. That was Marlowe, anonymous in print until after his death. But the period is full of writers without biographies and biographies without writers — I think it was Stephanie Hopkins-Hughes who first put it like that: writers, that is, without the biography of a writer — William Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon, for example, Edmund Spenser or John Webster. Edward de Vere falls into the second group, where we have a writer’s biography, but not the work. De Vere’s is absolutely the biography of a poet and playwright; he is acknowledged as such during his lifetime; but his work, apart from the juvenilia, is missing. It’s a very small step to wondering if we might have had it all along, under a different name — a pseudonym which turned into an allonym when Monsieur Jacques-Pierre turned up. Another member of the second group is Mary Sydney, sister of the poet Phillip Sydney, who likely wrote far more than she is credited with, and had every reason (her gender, for instance) for adopting a pseudonym or allonym. Hopkins-Hughes argues that she was, in fact, that dark and fascinating horror-poet of Jacobean theatre, John Webster.

Bacon, however, does not come into either category. He is a writer (among many other things) with a writer’s biography. We know his work, and it is considerable in scope, worthy of the time he gave to it, but there is no anomaly here, no real gap to fill. Delia Bacon, the first literary historian to open up the ‘Shakespeare Authorship Question’ two hundred years ago, for which she deserves immortal credit, wasn’t too far wrong in her theory. Although she is remembered for promoting the authorship of Francis Bacon, her theory actually promoted a group authorship. And Bacon had a great deal to do with it.

But there is very widespread agreement across all camps in the SAQ than in the spine of the Shakespeare oeuvre — the great works, culminating is his final revision of Hamlet — we sense a single unifying voice, an artistic and philosophical progression which denotes the journey of one man, one unruly spirit. And that Shakespeare I find it hard to imagine collaborating on his most important works. However, those eighteen unpublished plays are another matter. I suspect Shakespeare’s most productive collaborations, as it were, happened after his death.

de Vere JUVENILIA https://shakespeareoxfordfellowship.org/wp-content/uploads/DeVerePoemsJune2018pluscov.pdf

https://shakespearesolution.com/blog-articles/f/alexander-waughs-excellent-essay-on-oxford

Stritmatter https://shake-speares-bible.com/pdf/DVS_Audley_End.pdf

“The pulse of the dramatist is palpable in these notes, which pay close attention to moments of crisis, conflict, psychology and rhetoric, including many that are directly applicable to the design

and emphases of the two already named Roman plays.”

Thanks, Hank. I didn’t expect that…

I find your work interesting, but I don’t understand how you blame “the left” for the rejection of De Vere. The liberal-minded are not rejecting De Vere – it is the Conservative-minded who are rejecting the Authorship Question in the first place. Academia that wants to maintain the status quo is by definition Not Left, and the Stratford Birthplace Trust is taking a more than conservative view – they are downright reactionary. The entire Shakespeare industry has been used to prop up the decidedly not liberal status quo in Great Britain for centuries. But I think that overlaying the issue with the terminology of the modern political spectrum will ultimately serve no one. Better to concentrate on the merits of the SAQ and its inevitable answer than to actively court enemies. That said, I am genuinely curious to find where on the political spectrum Oxfordians are. Probably as varied as the various theories that are associated with the issue.

Yes, I’m getting a range of views on this, and I’ve provoked a few people. It’s based on my own experience, and my notion that de Vere should have a particular appeal to libertarians… as you say, overlaying contemporary terms has its problems. Thx.

Thanks for drawing my attention to J.L.Borges‘ Essay „Everything and nothing“.

I was surprised to read there : ….“but when the last line had been applauded and the last corps removed from stage, the odious shadow of unreality fell over him again: he ceased beeing … Tamburlaine and went back to beeing Nobody …..for 20 years he kept up this delirium…[then]..he returned to his hometown:: there he reclaimed the trees and the river of his youth without trying them to the other selves that his muse had sung, decked out in mythological allusions and latinate words. He had to be somebody and so he he became a retired impresario who dabbed in money-lending, lawsuits, and petty usury. It was as this character that he wrote the rather dry last will and testament …having purposefully expunged from it every trace of emotion and every literary flourish.“

When you notice that „Borges plays with the idea that William Shakespeare had the power to assume any identity he chose because he had no identity of his own“, you seem to have realized, that Borges was totally helpless in explaining the countless bizarre inconsistencies in the life of the Stratfordman.

Yourself you see the identity of the author (beyond reasonable doubts !) well founded now for a century by Looneys ground-breaking investigation. Was it really – a century later – only „the lazy, self-interested intransigence of Academia“, that Shakespeare’s [true] identity is still not widely known? –

There is a difference between Borges and yourself: He at least mentions the play „Tamburlaine“ of the greatest poet and dramatist of his time and of the same age as Shakspere..-You did not even consider it necessary , to at least mention the possibility of Shapespeare beeing a penname of Christopher Marlowe …. your religious ideology has already overgrown everything and nothing!

Be that as it may….

https://youtu.be/oHlCLMPK0zw?t=2

Interesting, the Tamburlaine reference – referring to WS as an actor, perhaps. I have certainly considered the case for Marlowe, don’t worry, but ultimately it’s unproductive . The identification of de Vere is proven by the evidence, which is growing all the time: nothing ‘religious’ about it. My piece is not about proving the case for de Vere – that’s already been done – but about considering its implications.

Brilliant work.

Thank you, my liege.