OF DOCTORS AND SHAMANS

We were talking about journeys, border-crossings, and shifting cultural identities.

Anissa is from the Congo. Not the big one, the Democratic Republic, formerly the Belgian Congo, synonymous with suffering — but its smaller neighbour, Republic of.

My Congo, she calls it.

‘When I am in my Congo,’ she says, ‘they call me La Parisienne. But here…’

She looks around at the peeling walls of the classroom. It’s a top-dollar school near Paris, set in beautiful grounds, though some of the buildings are surprisingly dilapidated. But the sweep of her eyes was meant to represent France — this multicultural society that is some way from having transcended racism.

‘When you go back,’ I ask, ‘do you feel you’ve changed? Do you still feel like you belong?’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I do, and I don’t.’

Which was perfect, allowing me to introduce the concept I was trying to get to, that of liminality — that is, an in-between or threshold state, on the boundary between two domains, realms, conditions, ages, statuses, whatever; the subject having left one set of classifications and not yet entered another.

I thought it would be a good topic for writing, giving the students an opportunity to write about themselves if they wanted to. Teenagers are an obvious example of liminality. They stand on a threshold, no longer children, not yet adults. And for these international kids there are cultural thresholds too.

But it also offered lots of imaginative possibilities. Liminal entities move in different worlds but belong in none, inhabiting the gaps, the interstices, the in-between. Ghosts, superheroes, mermaids and other chimaeras, vampires, centaurs and harpies, cyborgs and shamans.

The Russians and French in the class knew the word, but the Africans were unfamiliar.

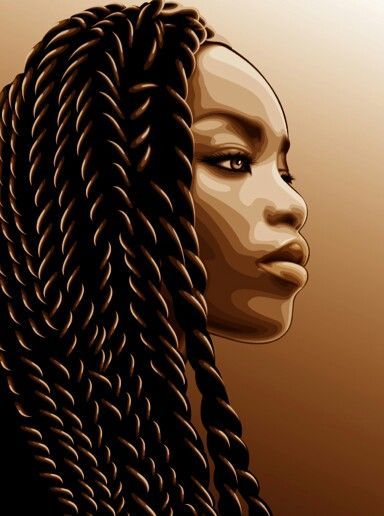

I threw up an image-search on the projector.

“The Shaman wears an animal skin or horns or feathers to make himself appear like a hybrid — it symbolises the ability to move between worlds, the human world and the spirit world.”

“Ah,” said Anissa. “Le Marabout.”

My only association with the word was the maribou stork, a big, ancient-looking bird with a bald head, an ugly, heavy beak and downy feathers cloaking its shoulders. In my mind’s eye I saw a shaman hopping around in a feathered cape with some kind of beak contraption attached to his face.

“Maribou?”

“Witch…

She turned those huge eyes to her friend Chrisvène, as if unsure of the term, and added,

“…doctor.”

Later I looked the word up and found that in Saharan and sub-Saharan countries it is used to refer to travelling Islamic scholars, but that’s not how Anissa was using it. It seems that further South it has attached itself to the shaman or ‘witch-doctor.’

I asked the students to think about what they wanted to write about out of all these ideas, and walked around chatting and answering questions.

When I got to Anissa I asked her to tell me more about the Marabout.

“Do people in your Congo go to the Marabout for help?”

“Yes,” she said. “He can find things that you have lost.”

“And what about healing?”

Chrisvène spoke up.

“You can go,” she said, “but it is dangereuse. You should only go if there is nothing else you can do.”

“Why is that?”

“Because he may steal something from you.”

“Like what?”

She looked at Anissa, who reached her hand up to the middle of my forehead and made a pinching movement with beautifully manicured fingers, drawing something away through the air like a thread, then turning her hand over as if to show me.

“Your… star,” she said.

I knew what she meant.

And when she said that, and made that gesture, for some reason the image of the stork-man disappeared from my mind’s eye and was replaced by a man in steel-rimmed glasses and a white butcher coat.

“Hmm,” I said. “I think the same may be true of some of our doctors here, in the West.”

It was only a throw-away remark as I was turning away to talk to other students, and I didn’t expect her to know what I meant, but she was nodding, widening, if that were possible, those enormous eyes.

It was early 2019. Two years later I remembered this conversation, and wondered if she remembered what I’d said.

I hoped so. She’d seemed to understand what I meant. even though I wasn’t sure myself.

Be careful, I want to say to those I know and love. He may steal something from you.

Your star.