The REBIRTH of THE AUTHOR

“There was no one in him; behind his face (which even in the poor paintings of the period is unlike any other) and his words, which were copious, imaginative, and emotional, there was nothing but a little chill, a dream not dreamed by anyone.”

Jorge Luis Borges, in his ultra-short story ‘Everything and Nothing’1, plays with the idea that William Shakespeare had the power to assume any identity he chose because he had no identity of his own. He becomes aware of his ailment and searches for relief from an aching sense of hollowness. He finds it in the theatre.

Instinctively, he had already trained himself in the habit of pretending that he was someone, so it would not be discovered that he was no one. In London he hit upon the profession to which he was predestined, that of the actor, who plays on stage at being someone else. His play-acting taught him a singular happiness, perhaps the first he had known; but when the last line was applauded and the last corpse removed from the stage, the hated sense of unreality came over him again. He ceased to be Ferrex or Tamburlaine and again became a nobody. Trapped, he fell to imagining other heroes and other tragic tales.

He enters the ‘controlled hallucination’ of writing, inventing myriad people to be, an escapist multiplicity to cover the ‘no one’ inside him:

Nobody was ever as many men as that man, who like the Egyptian Proteus managed to exhaust all the possible shapes of being.

Then one day he wakes up to the ‘surfeit and horror’ of being so many slain kings and unhappy lovers, and gives it all up. Returning to the village of his birth, he ‘recovered the trees and the river of his childhood; and he did not bind them to those others his muse had celebrated, those made illustrious by mythological allusions and Latin phrases.’ And so he sees out the rest of his existence imitating a ‘retired impresario who has made his fortune and who interests himself in loans, lawsuits, and petty usury.’ Only when friends from London come to visit does he slip again into the role of a poet. When he dies, he tells his maker: “I, who have been so many men in vain, want to be one man: myself.”

God replies: “Neither am I one self; I dreamed the world as you dreamed your work, my Shakespeare, and among the shapes of my dream are you, who, like me, are many persons — and none.”

Borges’ story is based on the surprising fact that almost nothing is known about the greatest poet in the English language and the greatest dramatist in world history – and that what is known about his life reveals nothing in the least bit interesting or suggestive of genius or literary ability of any kind. He focuses on the least convincing aspects of the conventional Shakespeare story — the inexplicable genesis of his art and, more than a decade before his death, his abrupt retirement both from the theatre world and from writing — to bring the story full circle, putting a post-modern gloss on the absurdity of the Shakespeare myth. The historical William Shakspere (sic) of Stratford-upon-Avon was a mediocrity – a run-of-the-mill businessman, broker and money-lender, a petty, litigious burgher who got a little rich. This paradox gives rise to Borges’ conceit: nothing less dramatic can be imagined than the life of the great dramatist.

Indeed, William Shakespeare is the Invisible Man of his time. His name on a title page or a dedication; a sole, ambiguous attribution by a contemporary; six signatures all spelled different ways. He owned no books, wrote and received no letters. He was never paid for what he wrote; never arrested either, unlike a number of his contemporaries; never questioned or tortured, even after the use of his work in support of the Essex rebellion.

The plays, of course, did not write themselves – but nor were they composed by Gulielmus filius Johannes Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon2, who by all indications was barely literate. The conventional assumption is that he must have received a grammar school education, but this is only an assumption since the enrollment records have not survived. William Shakespeare the writer, by contrast, had a world-class education and was deeply versed in every aspect of Renaissance humanism, as can easily be deduced from what he wrote.

The name Shakspere is most likely an anglicisation of the Norman Jacques-Pierre, and the wild variety of spellings of the name on extant documents seem to be creative attempts by third parties to transcribe it phonetically, with the soft J consistently approximated by ‘Sh’ but the consonant cluster and the final vowel causing all kinds of confusion — thus Shakspere, Shaxper, Shagspur and so on. It’s important to note that the A is always short, as in Jack, in the various versions of the Stratford man’s name that appear in documents. Pronunciation would have approximated to a collocation of ‘shack’ and ‘spare’ in modern orthography.

Shakespeare the poet, on the other hand, was always spelt with the middle E, making the A long and giving us the verb to shake. In nearly half of the surviving examples, the name was printed with a hyphen — SHAKE-SPEARE — which is the standard way of indicating a pseudonym, as with the anticlerical pamphleteer Martin Mar-Prelate, actually a group of Puritan satirists attacking the Anglican Church. The pseudonym was obviously chosen for its classical connotations: it derives from a soubriquet for the goddess Minerva or Pallas Athena, the ‘spear-shaker’. The two names are not the same, in spelling, pronunciation or provenance. But they are close enough for confusion, or misdirection.

I think Borges would have liked this version of the story almost as much: Will Shakspere of Stratford, this hollow man who does not know who he is, goes to London in the 1590s just as his near namesake bursts onto the literary scene, and finds that his name, or something like it, is on everyone’s lips. Sometimes in the taverns he’ll pass himself off as the poet, and once or twice it gets him laid. He picks up a few acting parts — non-speaking roles only, since he cannot read — and looks for business opportunities in the theatre world. But the best deal he ever makes is to sell his name as an allonym for this writer who already functions under a pseudonym, the misdirection creating a double layer of secrecy.3 And that’s as close as he ever gets to the real ‘William Shakespeare’, whoever this writer was who was spearheading the English literary renaissance through the medium of theatre. It was a walk-on part, like Rosencrantz or Guildenstern, with no chance of understanding the intrigues going on around him.

It is no surprise that the the writer in question went to such lengths to disguise his identity. He lived in a dangerous age for writers, the age of the Cecils, Archbishop Whitgift and the English Inquisition; the age of Elizabeth, Queen of Eyes and Ears. Pseudonymity is always tempting for writers, even in safer times: fiction, after all, is multiplicity, the prismatic refraction of personality. An author simultaneously reveals himself in his works and conceals himself behind them. Choosing a pseudonym is also an opportunity to create a brand: ‘Will Shake-speare’ was created as not just a nom-de-plume but also, like Martin Mar-Prelate, a nom-de-guerre, chosen for its defiant connotations — the brandishing of a spear before battle. And so the identity of ‘William Shakespeare’ remained a mystery for hundreds of years: he was the non-entity from Stratford; everything and nothing; everyone and no one.

In time the mystery would give birth not just to J L Borges’ quaint little story but to a fashionable post-modern theory of authorship, usually referred to in Roland Barthes’ formulation as ‘The Death of the Author’ (La Morte de L’auteur). This bizarre and depersonalising theory arose in the later twentieth century, but may (as a number of commentators have suggested) owe its provenance to the strange disjuncture between the works of William Shakespeare the dramatist and the uninteresting biography of William Shakspere of Stratford. Barthes and other fashionable intellectuals in the nineteen sixties argued that a writer’s life had no relevance whatsoever to the work, and promoted an ideology in which authors are merely unconscious or passive conduits for the culture and the language. Barthes may have been influenced by Borges’ story, for all I know; there’s not much more, essentially, to Death of the Author theory than an expansion of the Argentinian’s flight of fancy into a humorless theoretical model. If ‘it is the language that speaks’, in Mallarmé’s formulation, then the author has no authority, is merely a mouthpiece, and literature is reduced to sociology and linguistics. Like the citizen under Communism, the author is stripped of free will and authentic action. An even more unsettling retrospective on the theory would point out that the flesh-and-blood author becomes nothing but a foreshadowing or prototype of the Large Language Models of contemporary technology.

In any case, both Barthes in the sixties and Borges in the forties were lagging several decades behind the news: ‘Shakespeare’ had already been unmasked, not as some non-entity with infinite negative capacity and no identity of his own, but the opposite: very much someone, in fact. The Death of the Author was just a passing rumour: in the discovery of Shakespeare’s identity, the author really is reborn. The experience of rereading certain Shakespeare plays in its light is electric; we have been gifted a whole new writer — an even better one, deeper, more resonant, more real, more important than ever.

As a reader, unless you are a professional scholar, it’s hard to encompass such a vast body of work, and most Shakespeare enthusiasts end up knowing a handful of the plays, up to a dozen or so perhaps, rather well, usually the greatest plays that have really stood the test of time. You may have seen certain plays several times on stage or screen in different productions. If you’re a literature teacher you’ll have taught some of these plays a number of times, and there is no better way to become really familiar with a text than to teach it. Those who come to know the texts well tend to develop a strong sense of an individual voice, a singular sensibility and personality behind the plays, as indeed one would with any writer.

That was the case with J Thomas Looney (1870 – 1944), who taught Shakespeare throughout his career as a school-master, and in retirement decided to identify that personality, if at all possible, by drawing up a profile of the author’s discernable characteristics based purely on the works, and trying to find a match among historically documented individuals who were on the scene at the time at the birth of English theatre in Elizabethan London.

If, like me, you’ve always felt that unsettling disconnect between the works and their recognised author, it comes as a huge relief to read Looney’s profile; one is immediately struck by its unerring plausibility; it seems to represent a kind of rebirth of the individual in itself. Even before he puts a name on it, tentatively at first, one has a strong sense of the existence of this man taking shape: and he really is the opposite in every way of the mediocre stand-in we’d been forced to put up with for so long — at last, a Shakespeare worthy of the name. Looney’s instincts are good:

“Altogether we may say his poetic temperament and the exuberance of his poetic fancy mark him as a man much more akin mentally to Byron or Shelley than to the placid Shakespeare suggested by the Stratford tradition.” (110)

Looney’s exploratory reflections blast through the banality of the Stratford myth. We’re not looking for a respectable businessman but a wasted genius:

“For example, a man who has produced so large an amount of work of the highest quality, and was not seen doing it, must have passed a considerable part of his life in what would appear to others like doing nothing of any consequence. The record of a wasted genius is, therefore, what we might reasonably look for in any contemporary account of him.” (110)

We should not expect him to be universally popular:

The poetic genius has always been more or less a man apart, whose very aloofness is provocative of hostility in smaller men. (111)

And significantly, as it would turn out, Looney predicted that his relationship with the theatre would in real life turn out to be the opposite of the Stratford man’s: “It is much more reasonable to suppose that the dramatist was one who was prepared to give both himself and his substance to the drama, rather than one who was engaged in extorting a subsistence from it.” (114)

The profile in summary goes like this:-

“1. A matured man of recognized genius. 2. Apparently eccentric and mysterious. 3 Of intense sensibility, a man apart. 4 Unconventional 5 Not adequately appreciated 6 Of pronounced and known literary tastes 7 An enthusiast in the world of drama 8 a lyric poet of recognised talent 9 Of superior education — classical — the habitual associate of educated people.” (118-9)

Looney’s additional notes touch on the playwright’s Catholic leanings; his feudal, aristocratic perspective; his classical education; his enthusiasm for Italy; his fondness for aristocratic sports; his knowledge of and responsiveness to music; his financial profligacy and improvidence; and his conflicted relationships with women.

That’s quite a fully developed profile, which I think most Shakespeare readers would find highly plausible. Already we have a somewhat vivid portrait of the man, whoever he is. Out of this wealth of impressions, however, it’s a purely literary consideration which gives Looney the lead he is looking for. Shakespeare must have been known, he argues, if not for the dangerous and consequential enterprise of the plays, then surely as a lyric poet. In his early work, perhaps…

“His sonnets, Venus and Adonis and other lyric poems, place him easily amongst the best of the craftsmen in that art. Now, although his contemporaries may not have known that he was producing masterpieces of drama, it is extremely improbable that his production of lyric verse was as completely concealed. He may have hidden lengthy poems like Venus and Adonis or Lucrece, or brought them out under a nom-de-plume. But that no fugitive pieces of lyric verse should ever have gained currency under his own name is hardly possible.” (116)

Surveying the field of Elizabethan lyric poetry in the copious anthologies of the time, he came across an example by Edward de Vere which not only seemed to evince the sinuous logic and concinnity of the Shakespeare’s sonnets, but was written in the same stanza form as Venus and Adonis, i.e., a six-line stanza in iambic pentameter consisting of an alternately rhymed quatrain and a final rhyming couplet — like the sestet of a Shakespearean sonnet. Looney found that no less than seven of the twenty-two surviving lyric poems by de Vere scattered among various anthologies were written in this stanza. The imagery of the poem, too, seemed highly Shakespearean, the haggards metaphor recurring in a number of places in the plays.4

This is powerful internal evidence, which Looney was perhaps lucky to stumble on so early in his research, though this is probably more of a testament to his alertness and purposeful methodology. From there, everything falls inexorably into place as the book becomes a literary biography of the man — take him for all in all — who gave us the great works of Shakespeare. Looney’s investigation, Shakespeare Identified in Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (1920) is transparently presented, highly coherent, based on sound reasoning, deep knowledge of the works, and, I would say, a pretty unerring instinct; the book is also highly readable and its argument powerfully persuasive. His investigation establishes the identity of the author beyond reasonable doubt in my view, and provides a framework for a century of productive research by literary historians ever since.5

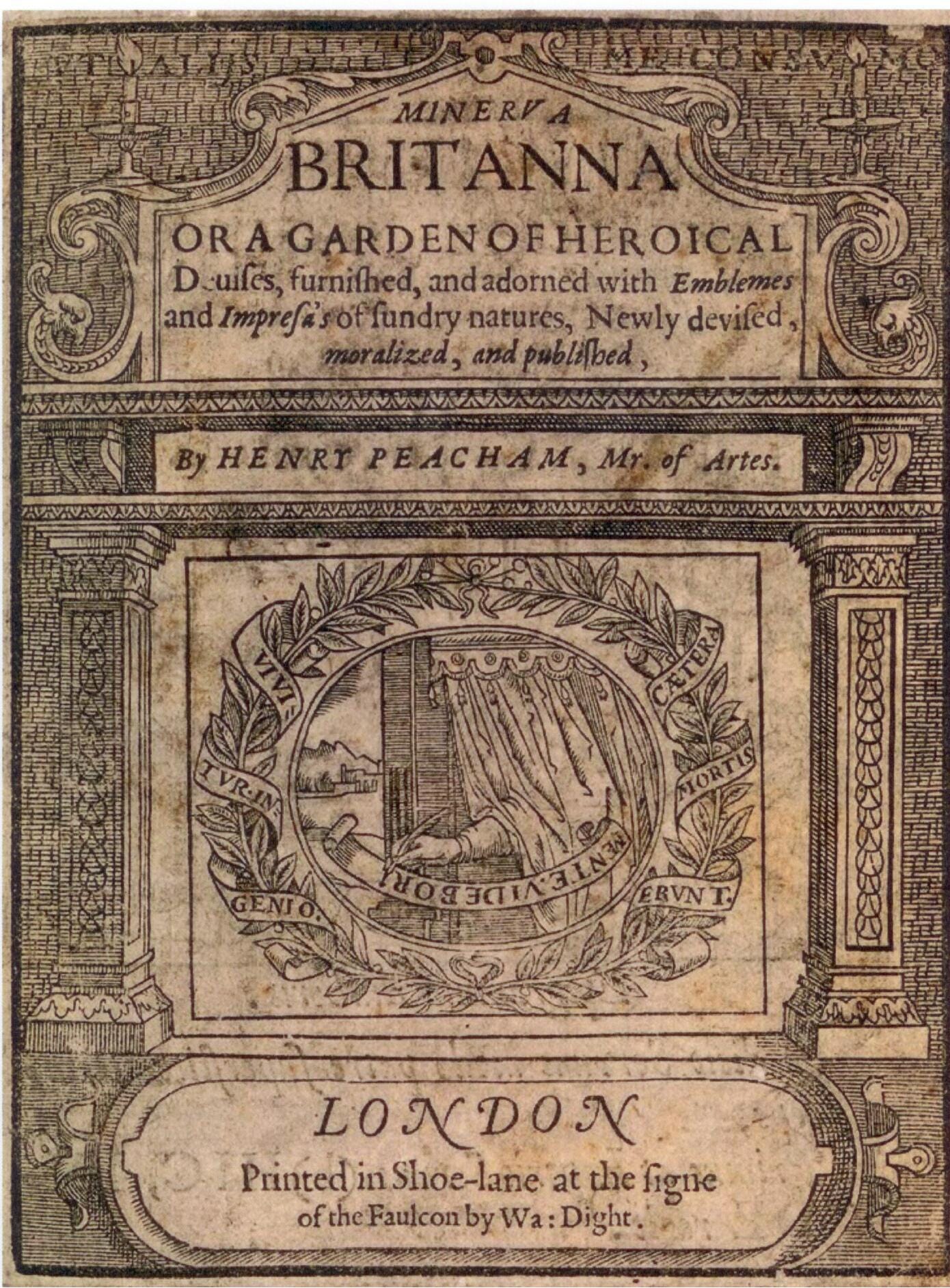

Insiders knew, of course, and more than a few cryptically acknowledged it to posterity and to each other in their works, as Alexander Waugh has documented in his Who Knew? series of video presentations. One of the most accessible of such contemporary references is the frontispiece of a book of emblems and devices, Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna (1612), which features a woodcut image reflecting the contemporary awareness of a concealed poet writing for the stage. A hand holding a pen emerges from behind a theatre curtain, and writes (upside down from our perspective to signify a code) the Latin words MENTE VIDEBORI (By the mind I shall be seen). It’s an anagram: NOM TIBI (your name is) DE VERE.

A more obscure though quite intriguing example has come down to us in the text of a Latin address delivered by the scholar Gabriel Harvey in 1578. In the course of a Royal Progress, Harvey delivered a public address in Latin before one of Elizabeth’s courtier-poets, the 28-year-old Earl of Oxford, Edward de Vere, in which he exorted the young man to abandon the pen for the sword and assume his martial destiny. The name William Shakespeare, of course, doesn’t appear in print until 1593, as a signature to the dedication of Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis to the Earl of Southampton. Certainly the 1593 publication marks the highly successful launch of a ‘new’ writer, whose fame rests on what he wrote (or rewrote) during the last decade of the sixteenth century and the opening years of the seventeenth. But there are intriguing hints that the pseudonym had been in use much earlier — from around 1577, Robert Prechter thinks — and Harvey’s oration is one of them:

Virtus fronte habitat: Mars occupat ora; Minerva

In dextra latitat: Bellona in corpore regnat:

Martius ardor inest; scintillant lumina: vultus

Tela vibrat: quis non redivivum iuret Achillem?

Valour dwells on thy brow: Mars possesses thy mouth: Minerva

In thy right hand lies hidden; Bellona in thy body reigns:

Warlike passion burns in thee; thine eyes flash: thy countenance

Shakes spears: who would not swear that Achilles was reborn?

Vultus tela vibrat: Thy countenance shakes spears. A coincidence? Perhaps, though ‘Minerva lies hidden’ in the same passage reduces the odds, introducing a context of secrecy. On the other hand, if Harvey was deliberately making the pun, why didn’t he use hastas (spears) rather than tela, which can refer to any projectile weapon?

It’s not a material point; just an intriguing reference which gives me my title, if nothing else. In any case, it should be emphasized that Looney’s argument does not depend on ciphers, codes, or anagrams, but on textual and literary evidence. Circumstantial evidence, copious as it is, comes in as corroboration, not as core argument, though it is remarkable, once the identification is made, how everything falls into place. The book is more than an exercise in historical detection: it’s a compelling creative history of the artist.

It is admittedly surprising to find such a reference so early in the timeline; it almost seems like foreshadowing rather than intelligence. It was only later, banished from the Court and his life torn apart by scandals and feuds, that the poet committed to the name under which his achievements in poetic drama would pass into history. But de Vere was involved in the theatre as a patron throughout his adult life, and was known to write and produce for his companies; he had performed in Commedia del Arte in Venice, and returned from his travels in the mid-seventies with detailed descriptions of the Italian theatres, which became the blueprint for the London play-houses, the first of which — The Theatre — opened in 1576, followed by The Curtain in ‘77. Harvey’s address, then, was given at a highly significant moment in the evolution of English theatre — and that, I don’t doubt, was why Elizabeth was not about to follow his advice by granting de Vere a military commission. She had other uses for him.

Within three years, however, he had been banished from the Court for his affair with Ann Vavasour, and remained in the cold for two years — during which time he established his own writers’ colony at Fisher’s Folly, the mansion he bought in London’s theatre district. His anomalous, déclassé status at this intensely creative and dangerous time in his life liberates him from class stereotypes, in my view, and puts him on the road to becoming the Shakespeare we know as the greatest literary artist in the language.

The identification with the non-entity from Stratford-upon Avon had always rankled, speaking for myself. I remember staring at that face and wondering how such intense masterpieces could originate in such a vapid gaze. In my youthful viewpoint, great writers must surely have strong personalities, should be contradictory and unpredictable, controversial and misunderstood. Monsieur Jacques-Pierre from Stratford was awfully disappointing in that respect. Edward de Vere, the scandalous seventeenth Earl of Oxford, by contrast, fits the role perfectly, emerging from his aristocratic background to become the first Bohemian in English culture, if you’re looking for one. One obviously has to be cognisant of one’s own prejudices: but regardless of preconceptions, the simple fact is that his biography is undeniably the biography of a writer, missing only the work itself — the lost oeuvre of Edward de Vere.

The whole thing becomes much more than a dispute about attribution; it’s an inquiry into the nature of art itself, specifically of fiction and the writer’s relationship to his work. The astonishing revelation that emerges is just how close is that relationship in the case of Shakespeare; the extraordinary extent to which de Vere drew on his own experiences, his own story. He may have started as a Tudor propagandist, but as time goes on his work becomes more and more personal, less and less containable. Who wrote Hamlet? Hamlet did.

De Vere is the answer to the riddle and the antidote to ‘Death of the Author’ theory. The problematic Earl was one of history’s great individualists, attracting much Puritanical opprobrium for his profligacy and bohemianism, his feuds and love-affairs. His creativity is about as far from a passive conduit as you can imagine; he didn’t just create his individual masterpieces, he did as much or more than anyone else to carve out the space, physical and cultural, in which they would be heard, pouring, as Looney puts it, his substance into the drama.

De Vere’s creative evolution is unique. In his late teens and early twenties he was Elizabeth’s favourite and a star performer at court, both in his own person and as the Puckish spirit behind brilliantly devised court entertainments. High-born and rebellious, driven, brilliant and reckless, his intimate relationship with the Queen allowed him to escape punishment for acts of defiance which would have had serious consequences for any other courtier. As becomes clear in the extraordinarily personal court drama of Hamlet, he saw himself as having the special status of a court jester or ‘licens’d fool’ in Elizabeth’s court. In the end that was only identity that he felt completely comfortable in — the Fool — and every fool in Shakespeare is de Vere.

After his return from Italy in 1576, he entered a period of intense turbulence in his personal life that would ultimately lead to his banishment from Court in 1581 (and ultimately becoming the plot of Othello). He had been flirting with expulsion from the magic circle for some time, and when disaster came, he responded with a fierce creativity and focus, recommitting himself to the drama, fully and defiantly embracing his literary destiny as the only identity he had left. If the banishment hadn’t happened, the poetic drama would never have become what it did. Looney stresses de Vere’s restlessness within the Court and his increasing Bohemianism, as he calls it, anachronistically perhaps. But Fisher’s Folly, the mansion de Vere acquired in the theatre district after his banishment, and where he brought together writers from all backgrounds, might legitimately be called the birthplace of Bohemia avant la lettre, and of a new literary style emerging from a potent cultural mix. The decade which began with de Vere’s expulsion from court saw a marked change in the character of English poetry, which ultimately stems from Lord Oxford’s immersion in London’s extramural theatre world. Looney writes:

We have already had to remark his restiveness under all kinds of restraints imposed by the artificiality of court life and his strong bent towards that Bohemian society within which were stirring energetic forces making for reality, mingled with much evil in life and literature. (162)

Quoting from Dean Church’s Life of Spenser, Looney characterizes the ‘Drab Age’ of English poetry as marked by “feebleness, fantastic absurdity, affectation and bad taste … Who could suppose what was preparing under it all? But the dawn was at hand.” (160)

De Vere’s exile has everything to do with this change. Looney cites Philip Sydney’s ‘In Defense of Poesie’ “as representing the earlier, feebler period, and the ‘rude playhouses with their troops of actors, most of them profligate and disreputable’ as being the source of the later and more virile movement.” (161)

The decade of the eighties constitutes “the period immediately following upon [de Vere’s] first poetic output, and it was during these years that he was in active and habitual association with these very troupes of play-actors […] What distinguishes Oxford’s work from contemporary verse is its strength, reality and true refinement. When Philip Sydney learned to ‘look into his heart and write’ he only showed that he had at last learnt a lesson that his rival had been teaching him.” (161)

During the next ten years, 1590-1600, “there burst forth suddenly a new poetry, which with its reality, depth, sweetness and nobleness took the world captive. The poetical aspirations of the Englishmen of the time had found at last adequate interpreters, and their own national and unrivaled expression.” (160)

The smoking gun for de Vere’s authorship is the autobiographical nature of his art. Looney comments on the irony that considering how long he kept himself concealed, we are going to end up knowing more about this man than anyone who ever lived. Not only him, of course: his perspective on every major figure in his life, friend or foe. That’s what made him so explosive; courtiers might smirk at the satirical portraits that are everywhere in the plays, but no one outside the Court could be allowed to penetrate its privacy in this way. As so often in social elites’ ruthless protection of the status quo, the reality principle itself ends up giving way — as in Borges’ fanciful story, or Barthes’ mechanistic theory.

De Vere’s self-portraits are just as unflinching. If his great studies in human folly are centred around his own person, this is not narcissism but rather its opposite. Tragedy, after all, is the study of how we destroy ourselves; in Hamlet, Othello and Lear, de Vere volunteers himself as the tragic model. This truthfulness, this devotion to reality no matter how uncomfortable, must have been one of the main reasons for the secrecy surrounding his identity, initially at least. It was more than just aristocratic convention and the stigma of print: the identity of the author, if known, would completely change the way his plays would be heard or read. The sonnets, explicitly autobiographical, wouldn’t be read at all, if the Privy Council could help it; when SHAKE-SPEARE’S SONNETS appeared (posthumously) in 1609, the publication was immediately banned and all copies rounded up and destroyed, with only a few dozen known to have survived.

So Shakespeare could only be read on the condition that we were not put in a position to fully understand him. And anonymity is what de Vere himself wanted; he makes that very clear in the sonnets. He wants his name, he says in Sonnet 72, to be buried where his body is. He actively wants to be forgotten, though he knows his work will survive under another name. And he got his wish, for three hundred years at least, until J T Looney pulled back the curtain. The irony is that his work would never fully come alive, in my view, until his identity as author was restored.

Without the correct attribution we lose unique insights into the structure of artistic revolutions, to adapt Thomas Kuhn’s famous book-title. Shakespeare’s drama represents such a significant paradigm shift that it wasn’t until the 19th century and the Romantic Revolution that his artistic influence really began to find receptors. Early Romantic-era writers like Coleridge, Hazlett and de Quincy recognised the significance of the work of the dramatist — and systematic inquiry into his identity follows immediately on from that period. Those who like to portray the status of Shakespeare as purely down to his imperialistic propaganda value should note that it was the Romantic individualists and non-conformists who rediscovered him as a writer, recognising their kinship with him — which was singularly not out of nationalistic worship for an establishment icon. Without them we might never have seen the growing awareness of the personality behind the works shown by a number of nineteenth century American writers and intellectuals — Hawthorne and Bacon, Whitman, Twain, and Emerson among them.

But even a century after J T Looney’s book, thanks to the self-interested inertia of academia and the stubborn resistance of commercial interests like The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, Shakespeare’s identity is still only known to a tiny fraction of those who know his name.

Much of the resistance de Vere’s authorship seems to reflect class prejudice, an inverted snobbery. De Vere is automatically to be rejected because of his birth: he is not the Shakespeare we want. We would prefer an idealised rags-to-riches figure, Mr Nobody from Nowhere, Dick Whittington with a talking cat. Instead what we get is Lord Byron with Faustian gifts and ‘lewd’ friends, the charismatic magnet for a Bohemian milieu in Venice and London. Sentimentalists don’t want to hear about this reckless aristocrat who got himself imprisoned in the Tower and then banished from Court. The final trigger was his affair with one of the Queen’s Maids of Honour, resulting in the birth of a bastard son and a vendetta pursued against him by relatives of the lady. The feud spilled onto the streets of Blackfriars in lethal brawls and ambushes, leaving three men dead and de Vere badly wounded. Such was the implosion of the child star of Elizabeth’s court.

For a decade at least, dating from soon after his marriage, his life was, you could say, dramatic: this period gave him the stories to which he returned in his ultimate self-exile from the Court, the years of seclusion during which he hammered out the final versions of his greatest works, turning them into literary as well as dramatic masterpieces – the great studies in human folly which became famous throughout the world. The classical masks and other metamorphoses which he found for his own dramas and traumas allowed him to write about his own life to a degree none of us ever associated with this period. In doing so he revolutionised the uses of fiction and moved literature into a new phase — which had to wait a couple of centuries, admittedly, for the world to catch up; and that is when questions began to be asked about who he actually was. The search for Shakespeare’s identity was contemporaneous with his rediscovery.

In the meantime, Stratford had become the chaste birthplace of a miracle, a kind of new Bethlehem. Will Shakspere goes to London and immediately starts producing masterpieces, without the foundation of education or any preparation in the form of experimentation or apprentice-work, leaving behind no juvenilia. Fifteen or so years later his genius is suddenly switched back off, and he doesn’t lift a pen again, leaving his unfinished works to be completed by hacks. This is not realistic; it’s a fairytale, or a flight of fancy by J L Borges. The reality is that de Vere’s masterpieces were achieved through a lifetime’s labour and were the result of both exuberant experimentation and painstaking revision. The ‘Shakespeare’ period of the 1590s and early 1600s, which have been traditionally seen as the explosion of Will Shakespeare’s youthful and implausible genius, turns out to have been the maturity of de Vere, who achieved his art through sweat, tears, and, yes, blood too.

It’s not just self-interest and inertia that keeps the Stratford fairy-tale alive, and it’s not just class resentment either. There is something deeper here as well, I believe; ultimately it’s the same impulse that lies behind ‘Death of the Author’ ideology. If a writer is nothing but an LLM, then how can any of us prove our existence as unique entities? It brings us one step closer to absorption into the machine. I’m talking about the abolition of the individual itself, as a concept, as a reality, as a moral centre – which Marshall McLuhan foresaw as the inevitable effect of the digital age. And that is our culture war.

The Stratford misdirection has always met with most opposition from writers, directors and other artists. Any real artist knows the labour of art; genius doesn’t just switch itself on and off like a light on a timer. Good writing is hard, long work, the work of an individual who is both equipped and impelled to write by his or her own history and psychology. Art is by definition individualistic and can come only from an individual, as an expression of unique identity. It is not a passive process. Genius is not magic.

In our celebrity culture, we want to believe that education, discipline and mastery are not preconditions for original creative production. We want to believe in achievement without effort, in ‘genius’ without discipline. That these plays somehow wrote themselves.

Today de Vere is no academic footnote, but a challenge to the engineering of contemporary culture. Just as secret performances of Shakespeare’s plays were staged by dissidents in Czechoslovakia under Communist tyranny, so de Vere’s clandestine art can sustain us in our own times. The Borgesian paradox is moot: Shakespeare was not nobody. He was a specific individual, unique and unrepeatable. Great art is not produced by impersonal cultural or historical forces, not by theory, and certainly not by technology. De Vere’s identification is death to the ‘Death of the Author’; in a word, the rebirth of The Author.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Everything and Nothing, by J. L. Borges

There was no one in him; behind his face (which even in the poor paintings of the period is unlike any other) and his words, which were copious, imaginative, and emotional, there was nothing but a little chill, a dream not dreamed by anyone. At first he thought everyone was like him, but the puzzled look on a friend’s face when he remarked on that emptiness told him he was mistaken and convinced him forever that an individual must not differ from his species. Occasionally he thought he would find in books the cure for his ill, and so he learned the small Latin and less Greek of which a contemporary was to speak. Later he thought that in the exercise of an elemental human rite he might well find what he sought, and he let himself be initiated by Anne Hathaway one long June afternoon. At twenty-odd he went to London. Instinctively, he had already trained himself in the habit of pretending that he was someone, so it would not be discovered that he was no one. In London he hit upon the profession to which he was predestined, that of the actor, who plays on stage at being someone else. His playacting taught him a singular happiness, perhaps the first he had known; but when the last line was applauded and the last corpse removed from the stage, the hated sense of unreality came over him again. He ceased to be Ferrex or Tamburlaine and again became a nobody. Trapped, he fell to imagining other heroes and other tragic tales. Thus, while in London’s bawdyhouses and taverns his body fulfilled its destiny as body, the soul that dwelled in it was Caesar, failing to heed the augurer’s admonition, and Juliet, detesting the lark, and Macbeth, conversing on the heath with the witches, who are also the fates. Nobody was ever as many men as that man, who like the Egyptian Proteus managed to exhaust all the possible shapes of being. At times he slipped into some corner of his work a confession, certain that it would not be deciphered; Richard affirms that in his single person he plays many parts, and Iago says with strange words, “I am not what I am.” His passages on the fundamental identity of existing, dreaming, and acting are famous.

Twenty years he persisted in that controlled hallucination, but one morning he was overcome by the surfeit and the horror of being so many kings who die by the sword and so many unhappy lovers who converge, diverge, and melodiously agonize. That same day he disposed of his theater. Before a week was out he had returned to the village of his birth, where he recovered the trees and the river of his childhood; and he did not bind them to those others his muse had celebrated, those made illustrious by mythological allusions and Latin phrases. He had to be someone; he became a retired impresario who has made his fortune and who interests himself in loans, lawsuits, and petty usury. In this character he dictated the arid final will and testament that we know, deliberately excluding from it every trace of emotion and of literature. Friends from London used to visit his retreat, and for them he would take on again the role of poet.

The story goes that, before or after he died, he found himself before God and he said: “I, who have been so many men in vain, want to be one man: myself.” The voice of God replied from a whirlwind: “Neither am I one self; I dreamed the world as you dreamed your work, my Shakespeare, and among the shapes of my dream are you, who, like me, are many persons — and none.”

[From Dreamtigers, by Jorge Luis Borges, translated by Mildred Boyer]

2 The only reference that connects Shakespeare with Stratford-upon-Avon is Ben Johnson’s ‘Sweet Swan of Avon’, in his First Folio encomium. However, the Brythonic name ‘Avon’, meaning ‘waters’ or ‘watery place’, as Alexander Waugh has shown, was used poetically at the time to signify not Stratford but Hampton Court: the ‘Sweet Swan of Avon’, Ben Johnson knew, was the poet of Elizabeth’s Versailles.

3 Robert Prechter’s speculation is that the deal was made in 1596, which is why the name ‘William Shake-speare’ began to appear on the title pages of plays in 1597 and ’98.

4 Poem No. 19: “If Women Could Be Fair and Yet Not Fond”

(renumbered as “E.O. 20” in Professor Stritmatter’s published study)

If women could be fair and yet not fond,

Or that their love were firm, not fickle still,

I would not marvel that they make men bond

By service long to purchase their good will.

But when I see how frail those creatures are,

I muse that men forget themselves so far.

To mark the choice they make and how they change,

How oft from Phoebus they do flee to Pan;

Unsettled still, like haggards wild they range,

These gentle birds that fly from man to man.

Who would not scorn and shake them from the fist,

And let them fly, fair fools, which way they list?

Yet for disport we fawn and flatter both,

To pass the time when nothing else can please,

And train them to our lure with subtle oath,

Till weary of their wiles ourselves we ease.

And then we say when we their fancy try,

To play with fools, oh what a fool was I.

Looney’s title: “Woman’s Changeableness”. Past commentaries on parallels: Looney (1920, 139-40, 163-64); Ogburn (380-81, 518); Sobran (266-67); Brazil & Flues; May (2004, 223-24, 228); Goldstein (2016, 53-54); Whittemore (55-58).

Source: Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship

5 Some of the most cutting-edge work in recent years has been done by Professor Roger Stritmatter in analysing the marginalia in de Vere’s Geneva Bible and their relationship to the play-texts, and more recently a similar investigation of the library at Audley End, near Saffron Walden in Essex, which is found to contain seven Elizabethan-era books annotated in de Vere’s hand, particularly those pertaining to Roman history.